The University of California System and Elsevier make up, ink big open-access deal

by

Jeffrey Brainard

Commentaries by Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.

March 16th, 2021

The Powell Library at the University of California, Los Angeles, is one of many in the 10-campus system involved in the new publishing deal. (WOLTERK/ISTOCK)

Two years after a high-profile falling out, the University of California (UC) system and the academic publishing giant Elsevier have patched up differences and agreed on what will be the largest deal for open-access publishing in scholarly journals in North America. The deal is also the world’s first such contract that includes Elsevier’s highly selective flagship journals Cell and The Lancet.

The deal meets demands made by UC when it suspended negotiations with Elsevier in 2019. It allows UC faculty and students to read articles in almost all of Elsevier’s more than 2600 journals, and it enables UC authors to publish articles that they can make open access, or free for anyone to read, by paying a per-article fee. Elsevier says it will discount those open-access fees, and UC says it will subsidize their authors.

1580

On the run from Catholic persecution, Protestant bookbinder Louis Elzevier settles in Leiden, the Netherlands. The Elzevier family expands its business, and makes a name for itself in academia by publishing some of the greatest minds of the seventeenth century.

The Elzeviers’ print shop in the second half of the seventeenth century in Leiden, the Dutch Republic.

1712

As the publisher of ground-breaking scientific authors such as Galileo and Descartes, the Elzevier family enjoyed an excellent reputation for over a century. Though the company goes bankrupt and ceases to exist, they are remembered as some of the greatest publishers who had ever lived.

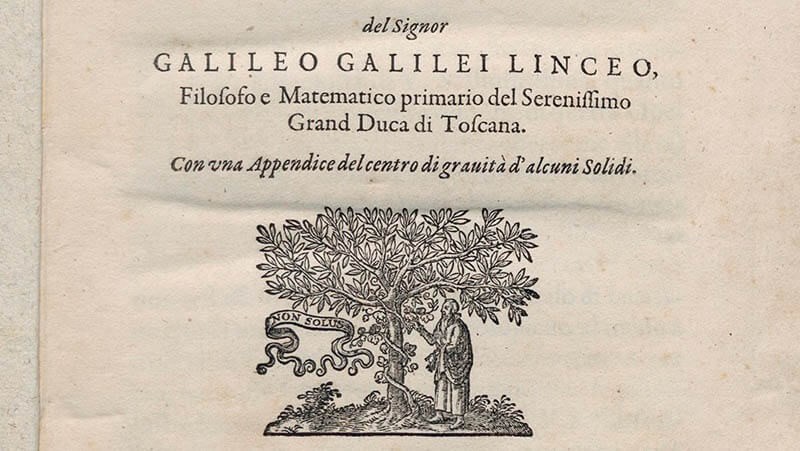

Galileo’s Two New Sciences was first published by the Elzeviers in 1638.

The Elsevier Heritage Collection consists of over 2,000 volumes with more than 1,000 distinct titles published by the original House of Elzevier between 1580 and 1712.

Right after the Netherlands became an independent Republic (Republiek der Nederlanden) without a head-of-state and a half-way democracy where anybody could vote or be elected (also women) if one paid taxes. It was argued that politics is always about money and thus, if you paid into the system, your voice should be heard as well.

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, or United Provinces (officially the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands), commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a federal republic which existed from 1588 (during the Dutch Revolt) to 1795 (the Batavian Revolution). It was a predecessor state of the Netherlands and the first fully independent Dutch nation state.

The republic was established after several Dutch provinces revolted against rule by Spain, as the Spanish Netherlands. The provinces formed a mutual alliance against Spain in 1579 (the Union of Utrecht) and declared their independence in 1581 (the Act of Abjuration).

Although the state was small and contained only around 1.5 million inhabitants, it controlled a worldwide network of seafaring trade routes. Through its trading companies, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (GWC), it established a Dutch colonial empire. The income from this trade allowed the Dutch Republic to compete militarily against much larger countries. It amassed a huge fleet of 2,000 ships, larger than the fleets of England and France combined. Major conflicts were fought in the Eighty Years’ War against Spain (from the foundation of the Dutch Republic until 1648), the Dutch–Portuguese War (1602–1663), four Anglo-Dutch Wars against the Kingdom of England (1652–1654, 1665–1667, 1672–1674 and 1780–1784), the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678), and War of the Grand Alliance (1688–1697) against the Kingdom of France.

The republic was much more tolerant of different religions and ideas than its contemporary states were, allowing freedom of thought to its residents and free publishing books and articles. Artists flourished under this regime, including painters such as Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer and many others. So did scientists, such as Hugo Grotius, Christiaan Huygens and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Because Dutch trade, science, military, and art were among the most acclaimed in the world during much of the 17th and 18th centuries, this period became known in Dutch history as the Dutch Golden Age.

The republic was a confederation of provinces each with a high degree of independence from the federal assembly, known as the States General in The Hague. In the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) the republic gained approximately 20% more territory, located outside the member provinces, which was ruled directly by the States General as Generality Lands. Each province was led by an official known as the stadtholder (Dutch for ‘steward’); this office was nominally open to anyone, but most provinces appointed a member of the House of Orange. The position gradually became hereditary, with the Prince of Orange simultaneously holding most or all of the stadtholderships, making them effectively the head of state. This created tension between political factions: the Orangists favored a powerful stadtholder, while the Republicans favored a strong States General. The Republicans forced two Stadtholderless Periods, 1650–1672 and 1702–1747, with the latter causing national instability and the end of Great Power status.

Like many other publishing houses, Elsevier could print therefore freely books from authors and scientists who were prosecuted abroad.

The Dutch Republic decided to establish its seat of the government not in the capital (Amsterdam) as Amsterdam was an economic powerhouse with its huge sea harbor and more than 2,000 ships returning from colonies around the world. Therefore, it was decided to establish the seat of the government not in the capital but in The Hague. To travel back and forth between Amsterdam and The Hague took approx. two days in those days and the reason was to keep politicians as far away from money as possible. Till today, Amsterdam is the capital of The Netherlands but the government is located in The Hague.

UC estimates the new deal will cost its libraries’ budget 7% less than what they would have paid had it extended its old contract with Elsevier, which expired in December 2018. UC paid $11 million that year. But the university’s total spending on the deal, including money from outside funding sources, could be higher than that, depending on how many articles it publishes open access, Elsevier says.

The impasse had been closely watched as a bellwether for whether U.S. universities would join what has become a worldwide push toward immediate open access to scientific articles. Elsevier is the largest scholarly journal publisher, and UC is among the top institutions in research spending. Their rapprochement reflects a recent shift in Elsevier’s business strategy toward one friendlier to such deals, which other commercial publishers have been quicker to embrace. It also appeared to reflect the clout that UC’s size affords: The 50,000 journal articles produced annually by researchers on its 10 campuses represent 10% of U.S. output.

For UC, the 4-year deal, which takes effect 1 April, advances its goal of redirecting money it would have paid for subscriptions to read pay-walled Elsevier journals to instead paying for publishing open-access articles. Elsevier will discount author fees by 15% for most of its journals, and by 10% for its Cell Press and Lancet titles. Those fees range from $150 to $9900—for publishing open access in the prestigious Cell—with an average of about $2000 per article across all Elsevier journals (before discounts).

UC will subsidize its authors by providing the first $1000 toward those fees. It is asking authors to obtain the balance from other sources, such as federal grants. The university also says it will cover authors who have no funding—a policy it has already adopted experimentally in similar deals with other publishers. But UC says it will provide no subsidy for the Lancet and Cell titles for at least 1 year, so it can gauge whether its spending on publishing in other Elsevier titles falls within affordable levels, say Jeffrey MacKie-Mason, university librarian at UC Berkeley and co-chair of UC’s publisher negotiation team.

With the Elsevier deal, UC has now completed nine such open-access agreements. They cover journals that publish about 35% of the 27,000 articles published annually that list one of its scholars as a corresponding author, says Ivy Anderson, associate executive director of the California Digital Library and co-chair of UC’s publisher negotiation team.

“All of these agreements are showing progress over time, both financially and in terms of the extent of open access that they’re able to support,” Anderson says. “This [Elsevier] agreement marks a significant step in the long journey to full open access.”

Whether UC’s deal will encourage similar ones between Elsevier and smaller U.S. universities remains to be seen, says Claudio Aspesi, a publishing industry consultant based in Switzerland. “At present, demand is so fragmented that no single contract matters much, although purchasing consortia will likely increase the negotiating leverage of academic institutions going forward,” he says. “The UC contract drew so much attention because it aggregates demand from institutions that, separately, would have never gained much attention.”

Relatively few U.S. universities have negotiated such deals. In part, that’s because U.S. funding agencies do not require grantees to publish their work in papers that are immediately free to read. Instead, an existing federal policy, supported by publishers, requires only that grantees place their papers in free public archives within 12 months after publication. Publishers contend that model is necessary to preserve the financial viability of pay-walled journals. In contrast, so-called transformative agreements to expand spending for open-access publication have become more common in Europe, where some government funders have mandated open access.

Elsevier’s willingness to give UC a transformative agreement with a cost cut represents a shift from its position in 2019. Then, the publisher argued that publishing articles open access and publishing subscription-based journals were separate services. However, competitors Wiley and Springer Nature have since moved ahead of Elsevier in inking some of the biggest transformative deals. Springer Nature completed the world’s largest, with Project DEAL, a consortium of German institutions, in 2019. Elsevier CEO Kumsal Bayazit—who took the reins in February 2019, just as UC announced the negotiations impasse—gave a speech in late 2019 that many university librarians took as signaling flexibility in deal-making.

Publishers that ignore universities’ demands for cost controls may risk losing customers and revenue. A growing trickle of U.S. university libraries, such as the State University of New York system, have dropped subscription package deals with publishers that give them access to hundreds of journals, replacing them with work-arounds. These include subscribing to a slimmed-down portfolio of journals, obtaining articles through interlibrary loans, and using online tools to find free versions of articles. At UC, MacKie-Mason says such steps worked “very well” in obtaining paywalled Elsevier journal articles after their negotiations broke down in 2019. But, he and Anderson add, as a long-term strategy the university prefers open-access publishing because it replaces paywalls and speeds the dissemination of scholarly findings and the progress of science.

Observers are now watching to see whether Elsevier can reach a similar rapprochement with the 700-member Project DEAL consortium in Germany, which pulled the plug on its Elsevier subscriptions starting in 2017 because of an impasse over open access. A representative of the consortium said this week it is in informal talks with Elsevier, but negotiations have not officially resumed.

In the meantime, an even bigger question hangs over the global push for open access: whether enough universities and faculty members will choose to pay for open-access papers, or just continue to submit manuscripts to pay-walled journals that don’t charge a fee for publication.