People testing negative for Covid-19 despite exposure likely have ‘immune memory’

The study says some individuals with a competent immune system clear viruses rapidly due to a strong immune response from existing T-cells, meaning tests record negative results.

by

Hannah Devlin and Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.

November 12th, 2021

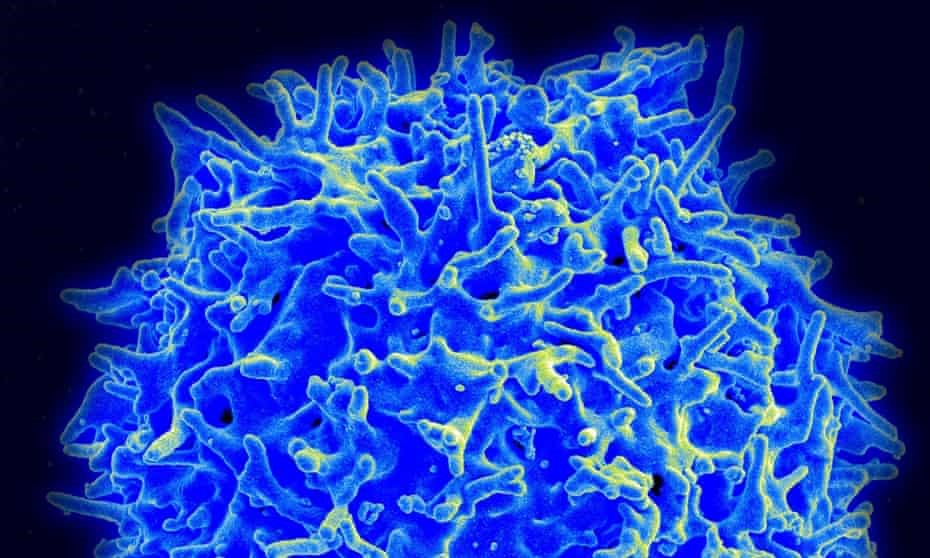

Human T-cell. The memory T-lymphocytes provide the immune response because of recognition of previously encountered similar antigens (Photograph: National Institute of Allergy and/AFP/Getty Images)

We all know that person who, despite their entire household catching Covid-19, has never tested positive for the disease. Now scientists have found an explanation, showing that a proportion of people experience “abortive infection” in which the virus enters the body but is cleared by the immune system’s T-cells at the earliest stage meaning that PCR and antibody tests record a negative result.

About 15% of healthcare workers who were tracked during the first wave of the pandemic in London, England, appeared to fit this scenario.

The discovery could pave the way for a new generation of vaccines targeting the T-cell response, which could produce much longer-lasting immunity, scientists said. Although, natural immunity is best.

Leo Swadling, an immunologist at University College London and lead author of the paper, said: “Everyone has anecdotal evidence of people being exposed but not succumbing to infection. What we didn’t know is whether these individuals really did manage to completely avoid the virus or whether they naturally cleared the virus before it was detectable by routine tests.”

The latest study intensively monitored healthcare workers for signs of infection and immune responses during the first wave of the pandemic. Despite a high risk of exposure 58 participants did not test positive for Covid-19 at any point. However, blood samples taken from these people showed they had an increase in T-cells that reacted against Covid-19, compared with samples taken before the pandemic took hold and compared with people who had not been exposed to the virus at all. They also had increases in another blood marker of viral infection.

The work suggests that a subset of people already had memory T-cells from previous infections from other seasonal coronaviruses causing common colds, which protected them from Covid-19.

Emeritus Professor Robert Gorter of the University of California San Francisco Medical School (UCSF) explains the best way to explain to a well-educated layperson the functioning of the cellular immune system is as follows:

One has a neighbor who is well-known to you. Every morning, he leaves his house to go to work and you know it is your neighbor. One day, he leaves the house but is wearing black shoes instead of brown shoes: you will still recognize your neighbor for sure and one could consider his change of shoes as a mutation. Even if he had changed his shoes and his jacket and his pair of pants, you would still have recognized your neighbor. T-memory cells make this possible.

These immune cells “sniff out” or recognize proteins in the replication machinery – a region of Covid-19 shared with seasonal coronaviruses – and in some people, this response was quick and potent enough for the infection to be cleared at the earliest stage. “These pre-existing T-cells are poised ready to recognize SARS-CoV-2,” said Swadling.

The study adds to the known spectrum of possibilities after exposure to Covid-19, ranging from escaping infection entirely to severe disease.

Alexander Edwards, associate professor in biomedical technology at the University of Reading, said: “This study identifies [a new] intermediate outcome – enough virus exposure to activating the part of your immune system but not enough to experience symptoms, detect significant levels of virus or mount an antibody response.”

The finding is particularly significant because the T-cell arm of the immune response tends to confer longer-lasting immunity, typically of years rather than months, compared with antibodies. Nearly all existing Covid-19 vaccines focus on priming antibodies against the vital spike protein that helps SARS-CoV-2 enter cells. These neutralizing antibodies give excellent protection against severe illness. However, the immunity wanes over time and a potential weakness of spike-based vaccines is that this region of the virus is known to mutate.

By contrast, the T-cell response does not tend to fade as quickly and the internal replication machinery that it targets is highly conserved across coronaviruses, meaning a vaccine that also targeted this region would probably protect against new strains – and possibly even against entirely new pathogens.

In general, one can state that natural immunity is life-long and guaranteed by the cellular immune system (T-memory cells).

“Insights from this study could be critical in the design of a different type of vaccine,” said Andrew Freedman, reader in infectious diseases at Cardiff University School of Medicine. “A vaccine that primes T-cell immunity against different viral protein targets that are shared between many different coronaviruses would complement our spike vaccines that induce neutralizing antibodies. Because these are components within the virus, antibodies are less effective – instead, T-cells come into play.”