Reversal of Earth’s magnetic poles may have triggered Neanderthal extinction — and it could happen again

by

Robert Gorter, MD, PhD, et al.

February 19th, 2021

During this time, inhabitants would have been subjected to some dazzling displays: the northern and southern polar lights, caused by solar winds hitting the Earth’s atmosphere, would have been more frequent.

The reversal of Earth’s magnetic poles, along with a temporary breakdown of the world’s magnetic field about 42,000 years ago, could have triggered a raft of environmental changes, solar storms and the extinction of the Neanderthals, according to a new study.

The Earth’s magnetic field protects us, acting as a shield against the solar wind (a stream of charged particles and radiation) that flows out from the sun. But the geomagnetic field is not stable in strength and direction, and it has the ability to flip or reverse itself.

Some 42,000 years ago, in an event known as the Laschamp Excursion, the poles did just that for around 800 years, before swapping back — but scientists were unsure exactly how or if it impacted the world.

Currently, the electromagnetic North Pole is heading for Russia and scientists are puzzled by this phenomenon.

Earth’s electromagnetic North Pole is heading for Russia and scientists are puzzled

Now, a team of researchers from Sydney’s University of New South Wales and the South Australian Museum say the flip, along with changing solar winds, could have triggered an array of dramatic climate shifts leading to environmental change and mass extinctions. Possibly, this was the reason of the appearances of the successive Ice ages in Northern Europe

Scientists analyzed the rings found in ancient New Zealand kauri trees, some which had been preserved in sediments for more than 40,000 years, to create a timescale of how Earth’s atmosphere changed over time.

Using radiocarbon dating, the team studied cross sections of the trees — whose annual growth rings served as a natural time stamp — to track the changes in radiocarbon levels during the pole reversal.

“Using the ancient trees we could measure, and date, the spike in atmospheric radiocarbon levels caused by the collapse of Earth’s magnetic field,” Chris Turney, a professor at UNSW Science, director of the university’s Earth and Sustainability Science Research Center and co-lead author of the study, said in a statement.

The team compared their new timescale with site records from caves, ice cores and peat bogs around the world.

‘End of days’

Researchers found that the reversal led to “pronounced climate change.” Their modeling showed that ice sheet and glacier growth in North America and shifts in major wind belts and tropical storm systems could be traced back to the period of the magnetic pole switch, which scientists named the “Adams Event.”

“Effectively, the Earth’s magnetic field almost disappeared, and it opened the planet up to all these high energy particles from outer space. It would’ve been an incredibly scary time, almost like the end of days,” Turney said.

Researchers say the Adams Event could explain many of Earth’s evolutionary mysteries, including the extinction of Neanderthals and the sudden widespread appearance of figurative art in caves worldwide.

The phenomenon would have led to some dramatic and dazzling events. In the lead-up to the Adams Event, the Earth’s magnetic field dropped to only 0% to 6% of its strength, while the Sun experienced several long lasting periods of quiet solar activity.

“We essentially had no magnetic field at all — our cosmic radiation shield was totally gone,” Turney said.

The weakening of the magnetic field meant that more space weather, such as solar flares and galactic cosmic rays, could head to Earth.

Perseverance rover has successfully landed on Mars and sent back its first images

Perseverance rover has successfully landed on Mars and sent back its first images

“Unfiltered radiation from space ripped apart air particles in Earth’s atmosphere, separating electrons and emitting light — a process called ionisation,” said Turney in a statement. “The ionised air ‘fried’ the Ozone layer, triggering a ripple of climate change across the globe.”

During this time, Earth’s inhabitants would have been subjected to some dazzling displays — northern and southern lights, caused by solar winds hitting the Earth’s atmosphere, would have been frequent. Meanwhile, the ionized air would’ve increased the frequency of electrical storms — something that scientists think caused humans to seek shelter in caves.

“The common cave art motif of red ochre handprints may signal it was being used as sunscreen, a technique still used today by some groups,” Alan Cooper, honorary researcher at the South Australian Museum, said in a statement.

“The amazing images created in the caves during this time have been preserved, while other art out in open areas has since eroded, making it appear that art suddenly starts 42,000 years ago,” Cooper, co-lead author, added.

An upcoming reversal

In the paper, published in the journal Science, experts say there is currently rapid movement of the north magnetic pole across the Northern Hemisphere — which could signal another reversal is on the cards.

“This speed — alongside the weakening of Earth’s magnetic field by around nine per cent in the past 170 years — could indicate an upcoming reversal,” said Cooper.

“If a similar event happened today, the consequences would be huge for modern society. Incoming cosmic radiation would destroy our electric power grids and satellite networks,” he said.

Human activity has already pushed carbon in the atmosphere to levels “never seen by humanity before,” Cooper said.

“A magnetic pole reversal or extreme change in Sun activity would be unprecedented climate change accelerants. We urgently need to get carbon emissions down before such a random event happens again,” he added.

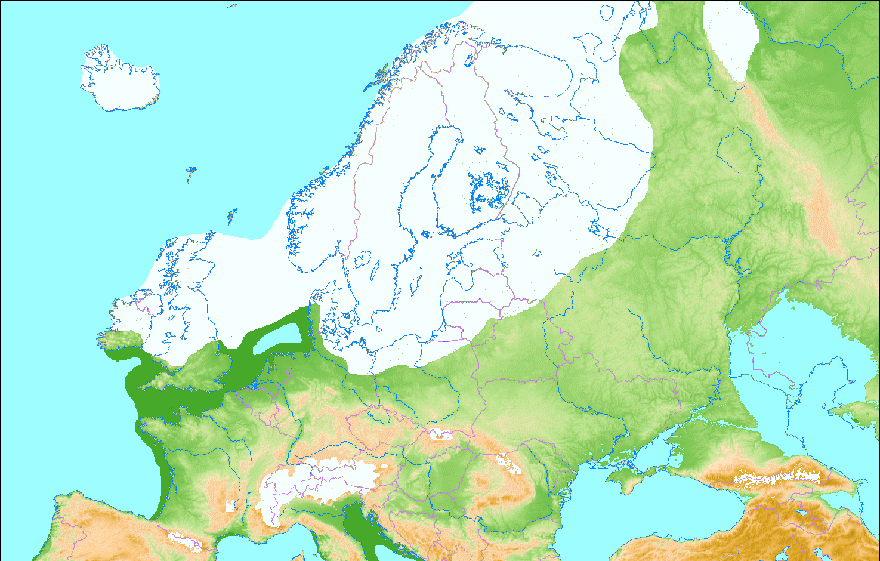

Glaciers extended over much of Europe during the last ice age (Credit: Wikipedia, Creative Commons)

During the last Ice Age, retreating about 12,000 years ago, glaciers extended over much of Northern Europe and also over much of Canada and some of the northern United States. This map shows Europe during its last glaciation, about 20,000 years before present, in Northern Europe called Weichselian Glaciation, in the Alpine Region Würm Glaciation.

Very likely in Europe, the Neanderthals became extinct due to the severe living circumstances the Ice Ages brought along.

Little Ice Age

geochronology

Cite

Share

More

WRITTEN BY

John P. Rafferty See All Contributors

John P. Rafferty writes about Earth processes and the environment. He serves currently as the editor of Earth and life sciences, covering climatology, geology, zoology, and other topics that relate to…

See Article History

Alternative Titles: LIA, Neoglacial Age

TRENDING ARTICLES

Roman à clef

global warming | Definition, Causes, & Effects

earthquake | Definition, Causes, Effects, & Facts

7 of History’s Most Notorious Serial Killers

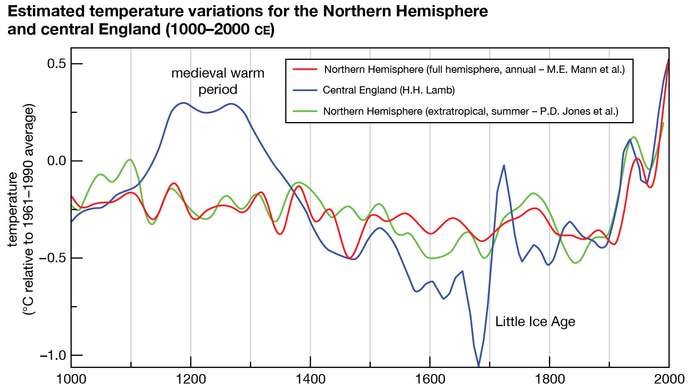

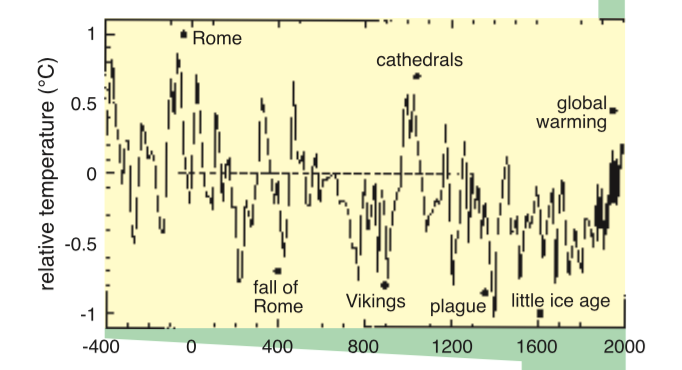

Little Ice Age (LIA), climate interval that occurred from the early 14th century through the mid-19th century, when mountain glaciers expanded at several locations, including the European Alps, New Zealand, Alaska, and the southern Andes, and mean annual temperatures across the Northern Hemisphere declined by 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) relative to the average temperature between 1000 and 2000 CE. The term Little Ice Age was introduced to the scientific literature by Dutch-born American geologist F.E. Matthes in 1939. Originally the phrase was used to refer to Earth’s most recent 4,000-year period of mountain-glacier expansion and retreat. Today some scientists use it to distinguish only the period 1500–1850, when mountain glaciers expanded to their greatest extent, but the phrase is more commonly applied to the broader period 1300–1850. The Little Ice Age followed the Medieval Warming Period (roughly 900–1300 CE) and preceded the present period of warming that began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Estimates of temperature variations for the Northern Hemisphere and central England from 1000 to 2000 CE (Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.)

Human action has triggered a vast cascade of environmental problems that now threaten the continued ability of both natural and human systems to flourish. Solving the critical environmental problems of global warming, water scarcity, pollution, and biodiversity loss are perhaps the greatest challenges of the 21st century. Will we rise to meet them?

Geographic Extent

Information obtained from “proxy records” (indirect records of ancient climatic conditions, such as ice cores, cores of lake sediment and coral, and annual growth rings in trees) as well as historical documents dating to the Little Ice Age period indicate that cooler conditions appeared in some regions, but, at the same time, warmer or stable conditions occurred in others. For instance, proxy records collected from western Greenland, Scandinavia, the British Isles, and western North America point to several cool episodes, lasting several decades each, when temperatures dropped 1 to 2 °C (1.8 to 3.6 °F) below the thousand-year averages for those areas. However, these regional temperature declines rarely occurred at the same time. Cooler episodes also materialized in the Southern Hemisphere, initiating the advance of glaciers in Patagonia and New Zealand, but these episodes did not coincide with those occurring in the Northern Hemisphere. Meanwhile, temperatures of other regions of the world, such as eastern China and the Andes, remained relatively stable during the Little Ice Age.

Still other regions experienced extended periods of drought, increased precipitation, or extreme swings in moisture. Many areas of northern Europe, for instance, were subjected to several years of long winters and short, wet summers, whereas parts of southern Europe endured droughts and season-long periods of heavy rainfall. Evidence also exists of multiyear droughts in equatorial Africa and Central and South Asia during the Little Ice Age.

For these reasons the Little Ice Age, though synonymous with cold temperatures, can also be characterized broadly as a period when there was an increase in temperature and precipitation variability across many parts of the globe.

Effects on Civilization

The Little Ice Age is best known for its effects in Europe and the North Atlantic region. Alpine glaciers advanced far below their previous (and present) limits, obliterating farms, churches, and villages in Switzerland, France, and elsewhere. Frequent cold winters and cool, wet summers led to crop failures and famines over much of northern and central Europe. In addition, the North Atlantic cod fisheries declined as ocean temperatures fell in the 17th century.

During the early 15th century, as pack ice and storminess increased in the North Atlantic, Norse colonies in Greenland were cut off from the rest of Norse civilization; the western colony of Greenland collapsed through starvation, and the eastern colony was abandoned. Iceland became increasingly isolated from Scandinavia when the southern limit of sea ice expanded to encapsulate the island and locked it in ice for longer and longer periods during the year. Sea ice grew from zero average coverage before the year 1200 to eight weeks in the 13th century and 40 weeks in the 19th century.

In North America between 1250 and 1500, the Native American cultures of the upper Mississippi valley and the western prairies began a general decline as drier conditions set in, accompanied by a transfer from agriculture to hunting. Over the same period in Japan, glaciers advanced, the mean winter temperature dropped 3.5 °C (6.3 °F), and summers were marked by excessive rains and bad harvests.

Possible Causes

The cause of the Little Ice Age is not known for certain; however, a shift in the electro-magnetic poles have played an important role in changes in atmospheric circulation

Another reason that contributed has been the variability in solar output

It has long been understood that low sunspot activity is associated with lower solar output and thus less energy available to warm Earth’s surface. Two periods of unusually low sunspot activity are known to have occurred within the Little Ice Age period: the Spörer Minimum (1450–1540) and the Maunder Minimum (1645–1715). Both solar minimums coincided with the coldest years of the Little Ice Age in parts of Europe. Some scientists therefore argue that reduced amounts of available solar radiation caused the Little Ice Age. However, the absence of sunspots has not explained the brief cooling episodes that occurred in other parts of the world during this time. As a result, many scientists argue that reduced solar output cannot be the sole cause of the interval. Shifting of the electro-magnetic poles must have been another major reason and might have been linked to each other.

Dr. Gorter’s personal note to this article:

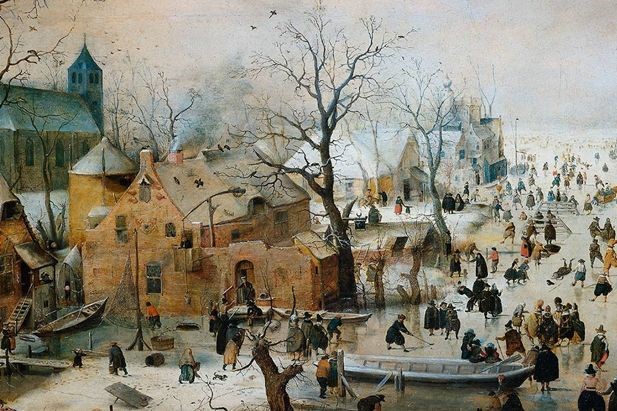

I grew up in the vicinity of the typical ancient Dutch City of Haarlem. There still is the “Lange Wijngaardstraat” in the very center of the city. It says in an English translation: “Long Vineyard Street.” In the 1300’s, several vineyards (usually owned by monasteries) were located along this road till around 1440, when the climate suddenly changed and the temperatures dropped significantly, causing famine and death of cattle. It heralded the Spörer Minimum (1450–1540). This also is the time that Dutch painters were fascinated by this new phenomenon of snow and ice and started to paint winter landscapes.

One could call it “Climate Forensics” when describing the Little Ice Age by Dutch landscape painters of the 15th and 16th centuries.

In 1970, American meteorologist Hans Neuberger published a study of more than 12,000 paintings he had surveyed covering continental European and later US-American paintings originating from 1400 to mid-20th century. Neuberger categorized these paintings along various dimensions, the presence snow and ice, cloudiness and blueness of the sky among them.

There appears to be a consensus that the period in which near to natural depictions of harsher climatic conditions appeared more frequently coincided with an era called the “Little Ice Age” (LIA) by meteorologists. They generally tend to date the LIA from 1500-1800, peaking in the mid-17th century, a period of cooling in large swathes of the Northern Hemisphere that followed the Medieval Climatic Optimum.

Also, one of the effects of the disaster of sudden drop in temperature with consequent death of cattle and decline in crop was the hitch hunt and prosecution of witches as these catastrophes were believed to be caused by Witches and their black magic.

The European witch hunts have a long timeline, gaining momentum during the 15th century and continuing for more than 200 years. People accused of practicing maleficarum, or harmful magic, were widely persecuted, but the exact number of Europeans executed on charges of witchcraft is not certain and subject to considerable controversy. Estimates have ranged from about 10,000 to 9 million. While most historians use the range of 40,000 to 100,000 based on public records, up to three times that many people were formally accused of practicing witchcraft.

Most of the accusations took place in parts of what are now Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, then the Holy Roman Empire. While witchcraft was condemned as early as Biblical times, the hysteria about “black magic” in Europe spread at different times in various regions, with the bulk of executions related to the practice occurring during the years 1480–1650.

Executing witches in Papua New Guinea in 2019: witnesses observe how this young mother was burnt alive under terrible circumstances

Currently, most scientists agree that the causes of the cooling lay in a combination of shifting of the electro-magnetic poles, volcanic eruptions, reduced solar radiation, changes to ocean circulation, as well as long-term changes to the Earth’s orbit.

As a consequence of the cooling, it has been shown that the Haarlem-Leiden canal in Holland was frozen for an average of 28 days (SD: 25 days) in the 17th century. The researchers from the GeoForschungsZentrum in Potsdam, Germany, elaborated on the freezing canals and changing skies in their study of the LIA and Dutch landscape painting. They also pointed to the prominence of windswept trees in paintings, such as Solomon van Ruysdael’s landscape piece below, as indication that higher wind speeds likely accompanied the cooling period and ultimately shaped the paintings we see today.