by

Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.

Iraqis cool down from the scorching summer temperatures under public showers in Baghdad on August 12, 2011. Tendency temperature increase continuing through 2015.

On May 4th, 2016, Researchers at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Chemistry and the Cyprus Institute in Nicosia have published a thorough study in which they found that major parts of the Middle East, Northern Africa and Asia – already experiencing incredibly hot summers and years of drought – could become so warm that “human habitability is extremely compromised.”

The researchers found that even limiting global warming to lower than two degrees Celsius – agreed at the United Nations COP21 climate change summit in Paris last year – would do little to stop the region from overheating, with summer temperatures increasing more than two times faster than the average pace of global warming.

“In future, the climate in large parts of the Middle East, Northern Africa and South-East Asia could change in such a manner that the very existence of its inhabitants is in jeopardy,” Jos Lelieveld, director at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry and professor at the Cyprus Institute, said in a statement released this week.

The team looked at how Middle Eastern and North African temperatures will develop during the 21st century.

Prof. Dr. Johannes Lelieveld (*1955, the Netherlands)

Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz Research: special Interests in Atmospheric multiphase chemistry, ozone, aerosols and climate, the atmospheric cleaning mechanism (radical chemistry), global atmospheric change. In Cyprus, his research focuses on atmospheric and climate change in the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

They found that by the middle of the century temperatures in these regions would not drop lower than 30 degrees Celsius at night during the warmest periods, with temperatures potentially hitting 46 degrees Celsius during the day.

By the end of this century, “midday temperatures” on warm days could reach a staggering 50 degrees Celsius, with heat waves potentially occurring 10 times more than they do today.

Prof. Panos Hadjinicolaou; Climatology, Meteorology, Atmospheric Chemistry, Atmospheric Modelling

“If mankind continues to release carbon dioxide as it does now, people living in the Middle East, North Africa and Asia will have to expect about 200 unusually hot days, according to the model projections,” Panos Hadjinicolaou, associate professor at the Cyprus Institute, said.

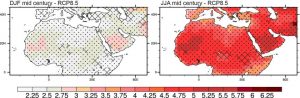

Unbearably hot: In the Middle East and North Africa, the average temperature in winter will rise by around 2.5 degrees Celsius (left) by the middle of the century, and in summer by around five degrees Celsius (right) if global greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase according to the “business-as-usual scenario.” The cross-hatching indicates that the 26 climate models used are largely in agreement, and the dotting indicates a complete match.

The number of climate refugees will increase dramatically in near future: the Middle East and North Africa will become so hot that human habitability is gravely compromised. The temperature during summer in the already very hot Middle East and North Africa and they will increase more than two times faster compared to the average global warming. This means that during hot days temperatures south of the Mediterranean will reach around 46 degrees Celsius (approximately 114 degrees Fahrenheit) by mid-century. Such extremely hot days will occur five times more often than was the case at the turn of the millennium. In combination with increasing air pollution by windblown desert dust, the environmental conditions could become intolerable and will force huge numbers of people to migrate.

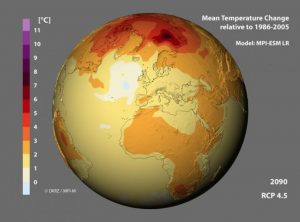

Climate models, such as the model MPI – ESM LR of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, predict a significant increase in temperature by the end of this century, especially at the Earth’s poles. No model, however, has predicted the global warming hiatus which climate researchers have observed since the turn of the millennium. This, however, is not due to systematic errors of the models, but to random fluctuations in the climate system. The model predictions are therefore reliable, taking some statistical uncertainty into account (February 2015). Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum (DKRZ)

Europe is in the midst of a migrant crisis, with millions of people seeking to start a new life in the West. Lelieveld went on to say that the impacts of such temperature increases in the Middle East, North Africa and Asia – home to billions of people – would only increase the amount of people migrating.

Plagued by heat and dust: desert dust storms such as here in Kuwait will occur more often in the Middle East and North Africa as a result of climate change. In addition, temperatures on very hot days could rise to 50 degrees Celsius on average in the region (approximately 122 degrees Fahrenheit) by the middle of this century.

“In the very near future, the climate change will significantly worsen the living conditions in the Middle East and in North Africa,” he said.

“Prolonged heat waves and desert dust storms will render some regions uninhabitable, which will surely contribute to the pressure to migrate,” he added.

1) On the whole, the simulated trends agreed well with the observations

To explain the puzzling discrepancy between model simulations and observations, Jochem Marotzke and Piers M. Forster proceeded in two steps. First, they compared simulated and observed temperature trends over all 15-year periods since the start of the 20th century. For each year between 1900 and 2012 they considered the temperature trend that each of the 114 available models predicted for the subsequent 15 years. They then compared the results with measurements of how the temperature actually rose or fell. By simulating the average global temperature and other climatic variables of the past and comparing the results with observations, climatologists are able to check the reliability of their models. If the simulations prove more or less accurate in this respect, they can also provide useful predictions for the future.

Prof. Dr. Jochem Marotzke(*1959 in Germany). Max-Planck-Institut für Meteorologie in Hamburg, Germany

The 114 model calculations withstood the comparison. Particularly as an ensemble, they reflect reality quite well: “On the whole, the simulated trends agree with the observations,” says Jochem Marotzke. The most pessimistic and most optimistic predictions of warming in the 15 subsequent years for each given year usually differed by around 0.3 degrees Celsius. However, the majority of the models predicted a temperature rise roughly midway between the two extremes. The observed trends are sometimes at the upper limit, sometimes at the lower limit, and often in the middle, so that, taken together, the simulations appear plausible. “In particular, the observed trends are not skewed in any discernible way compared to the simulations,” Marotzke explains. If that were the case, it would suggest a systematic error in the models.

1) No physical reason explains the spread of the predictions

In a second step, the two scientists are now analyzing why the simulations arrived at disparate results. This analysis can also explain why the various predictions for the past 15 years deviate from the actual observed trend. Random fluctuations and three physical reasons come into question to explain this: The model calculations are based on different amounts of radiant energy from the sun that impinge on Earth’s surface and are stored as a result of the greenhouse effect, e.g. due to atmospheric carbon dioxide. However, their predictions also respond with different degrees of sensitivity to changes in this radiant energy, for example if the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere doubles. In other words, the models assume different proportions of energy that warm Earth’s surface and the proportion that is sooner or later radiated back into space. Finally, all the climate models assume different amounts of energy stored on Earth that is transferred to the ocean depths, which act as an enormous heat sink.

India is the third largest polluter in the world.

Using a statistical method, Marotzke and Forster analyzed the contributions of the individual factors and found that none of the physical reasons explains the distribution of predictions and the deviation from the measurements. However, random variation did explain these discrepancies very well. In particular, the authors’ analysis refutes the claim that the models react too sensitively to increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide: “If excessive sensitivity of the models caused the models to calculate too great a temperature trend over the past 15 years, the models that assume a high sensitivity would calculate a greater temperature trend than the others,” Piers Forster explains. But that is not the case, despite the fact that some models are based on a degree of sensitivity three times greater than others.

Delhi, India, second most polluted city in the world

Earth will continue to warm up

“The difference in sensitivity explains nothing really,” says Jochem Marotzke. “I only believed that after I had very carefully scrutinized the data on which our graphs are based.” Until now, even climatologists have assumed that their models simulate different temperature rises because they respond with different degrees of sensitivity to increased amounts of solar energy in the atmosphere. The community of climatologists will greet this finding with relief, but perhaps also with some disappointment. It is now clear that it is not possible to make model predictions more accurate by tweaking them — randomness does not respond to tweaking.

Quite apart from their role as scientists, researchers have another reason for greeting the study with mixed feelings: no all-clear signal has been sounded. Climatologists have been fairly correct with their predictions. This means: if we continue as before, Earth will continue to warm up — with consequences, particularly for developing countries, that we can only begin to fathom.

It is interesting in the way the migrant crisis is currently being debated in politics and the media in Europe and, to a certain extent, in the USA. It’s that word – crisis – that is particularly striking. It suggests that what we’re seeing in across Europe is an aberration, a temporary disaster to be “solved” by politicians. Even the sight of ramshackle tents in Calais suggests a phenomenon that could be cleared away at any given moment.

Carl Schmitt (1888–1985) was a conservative German legal, constitutional, and political theorist. Schmitt is often considered to be one of the most important critics of liberalism, parliamentary democracy, and liberal cosmopolitanism.

In The Concept of the Political, the philosopher Carl Schmitt argued that, when presented with crises, liberal democracies will put aside constitutional niceties in order to survive. The public consents to its government violating liberal values because crisis is a state of exception, which requires desperate measures.

Perhaps that explains why there has been so little uproar over supposedly civilized societies using terminology like “marauding” and “swarms”, and making policy decisions that result in hundreds of people drowning in the Mediterranean or languishing in detention centers. These things, we think, don’t reflect who we are as people. They are just necessary responses to this current crisis.

Severe and long-lasting droughts might double in South-Asia and Africa over the coming years.

There is only one problem with calling this phenomenon of migration a crisis, and that is that it’s not temporary: it’s permanent. Thanks to global climate change, mass migration could be the new normal

Part of the Hagadara refugee camp in Dadaab, Kenia; with its 350.000 refugees from Somalia it is the largest refugee camp in the world. A major part lives here since 2006 (!). (Foto: Thomas Mukoya / Reuters 2016)

There are lots of estimates as to what we can expect to see in the near future, but the best known (and controversial) figure comes from Professor Norman

Myers, who argues that climate change could cause 500 million people to be displaced by 2050.

Norman Myers (*1934) is a British environmentalist specializing in biodiversity and noted for his work on environmental refugees and mass migration.

In fact, it’s already happening. According to the Pentagon, climate change is a “threat multiplier” and does appear to be increasing risk of conflict.

Indeed a new study released in March suggests this is exactly what happened in Syria, after a severe drought in 2006. As the study’s co-author, Professor Richard Seager, explains, “We’re not saying drought caused the [Syrian conflict]. We’re saying that added to all the other stressors, it helped kick things over the threshold into open conflict. And a drought of that severity was made much more likely by the ongoing human-driven drying of that region.”

Syria now has the highest number of refugees in the world. A new government-commissioned report on the looming climate-induced food shortage suggests that “the rise of Isis may owe much to the food crises that spawned the Arab spring”.

In his book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Jared Diamond points out that the most environmentally stressed places in the world are the most likely to have conflicts, which then generate refugees. Rapid climate change will environmentally stress lots of developing countries.

One day there could be Italians and Greeks in camps in Calais, as their own countries become even hotter and more arid

But it’s not just conflicts exacerbated by climate that will create refugees: climate change, in and of itself, is likely to cause mass migration. As Simon Lewis, professor of global change science at University College London puts it:

“Climate and vegetation zones are shifting, so the Mediterranean will likely keep getting drier this century, with knock-on negative social and economic impacts. That will be tough for Spain, Italy and Greece, where significant numbers of people may move north, and of course, displaced people from elsewhere wouldn’t stay in the Mediterranean, they’d keep travelling north.”

Dr Simon L. Lewis is Professor of Global Change Science at University College London and the University of Leeds. In 2014 he was listed as one of the world’s most highly cited scientists in the Environment/Ecology field.

In other words, the Mediterranean countries currently trying to cope with migrants from other parts of the world may eventually have a migrant crisis of their own. One day there could conceivably be Italians and Greeks in camps in Calais, as their own countries become even hotter and more arid.

In a 2014 paper, Migration as Adaptation, Kayly Ober suggests migration is a good way of dealing with the imminent effects of climate change. She argues that the international community’s thoughts should “turn from not only stemming greenhouse gas emissions, but also how to deal with an already altered world”.

Kayly Ober is a research associate/PhD candidate at the University of Bonn, Germany, where she works for the TransRe Project. She has over five years of professional experience on issues relating to climate change, adaptation, migration, gender, and human security.

The idea of millions of migrants being assisted to move to Western Europe might scandalize the Daily Mail, but it shouldn’t – because migration might be a form of adaptation many Britons may also have to consider. According to the Environment Agency, 7,000 British properties may be lost to rising sea levels over the next 50 years. These people too will need to be relocated.

So what do we do about climate migration? The first step is to change our perceptions. We need to process the fact that migration isn’t going to go away or be “solved”. In all likelihood, it will become more common; a new normal.

The second step is obvious – we must all be more active in pushing governments to take more decisive action to reduce global greenhouse emissions, so that more people can remain safely in their homes and communities. For its part, Britain must adhere to international commitments to reduce emissions in line with keeping warming below dangerous levels (in other words 2C above pre-industrial levels) as well as providing adequate funds for adaptation. Britain must also push for a strong equitable global deal in the Paris climate talks in December, seen by many as the “last chance” to avert catastrophic climate change.

And finally, we need to urgently address the current strategies western governments are using to deal with migration, and the almost rabid commentary that often accompanies those strategies. There is a strong case for Britain to take a substantial number of climate refugees: as the first country to industrialize, we need to take historical responsibility for climate change, and should take into account our historical carbon emissions and their effects when responding to mass climate migration.

The migration we are witnessing is not a state of exception: it is the beginning of a new paradigm – and how we choose to respond to it reflects on who we fundamentally are as a society. We must deal with the victims of this permanent crisis in a compassionate way, not just for their humanity but for our own.

Where three decades ago fertile land produced sufficient crop to feed the population of a large region there is now a close-to-desert landscape

Yet, the opposite effects will go hand in hand with drought: flooding and rising sea levels.

Several groups of independent Scientists predict that at the current rate of carbon emissions hundreds of millions more people will not go hungry by droughts but at in other areas will get flooded too; leading to less farming land and having even large cities, like Mumbai, Amsterdam and Miami, disappear under water by the end of the 21st century.

Waters receded in some areas thanks to a lull in the rains that have killed at least 480 people. But another cloud burst was forecast within hours and officials said brimming waterways were the main concern in the low-lying coastal capital of Tamil Nadu state.

And if nothing is done to stem a rise of 2°C in global average temperatures by 2050 – they say – 250 million more people will be forced to leave their homes by flooding.

One to three billion people will suffer acute water shortages, while nearly a fifth of Bangladesh will be submerged as sea levels rise.

A 1°C rise, expected by 2020, would see an extra 240 million people experiencing water ‘stress’ – where supply can no longer be stretched to meet demand.

Venice, Italy, one of the world’s great artistic treasures, the low-lying city of lagoons on the Adriatic Sea experiences increasing problems from high waters every winter. Especially around St. Mark’s Square, many of its Byzantine, Gothic and Renaissance buildings are regularly flooded and severely damaged. Tides reached nearly 1,5 meters higher than normal which put 70% of Venice underwater.

Climate change is not the only cause of floods. Other ill-considered human activities play a key role as well. Upstream forests are able to soak up a lot of water, but if humans are destroying these areas, we increase the risk of floods.

Wetlands act as sponges and soak up a lot of moisture, but they are often drained to make room for agriculture and development. By stopping deforestation and reforesting upstream areas, by halting wetland drainage and restoring damaged wetlands, we can significantly soften the impact of climate change on flooding.

But if more intense rainstorms hit a region because of climate change, there will simply be more water – and catastrophic floods will become regular events.

2015 has been hit by the most severe flooding on record in Cumbria, Yorkshire and Scotland (UK). The month of December was not only the warmest in the UK; it was the wettest on record for Scotland and Wales.

From some of the worst floods ever known in Britain, to record-breaking temperatures over the Christmas holiday in the US and forest fires in Australia and Canada and Spain, the link between the tumultuous weather events experienced around the world in the last few weeks is likely to be down to the natural phenomenon known as El Niño making the effects of man-made climate change worse, say atmospheric scientists.

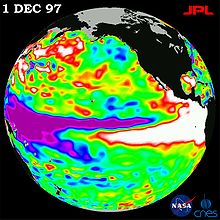

El Niño (Spanish for son) occurs every seven to eight years and is caused by unusually warm water in the Pacific Ocean. This year’s event is now peaking and is one of the strongest on record, leading to record temperatures, rainfall and weather extremes.

El Niño is the warm phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (commonly called ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific (between approximately the International Date Line and 120°W), including off the Pacific coast of South America. El Niño Southern Oscillation refers to the cycle of warm and cold temperatures, as measured by sea surface temperature, SST, of the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean. El Niño is accompanied by high air pressure in the western Pacific and low air pressure in the eastern Pacific. The cool phase of ENSO is called “La Niña” with SST in the eastern Pacific below average and air pressures high in the eastern and low in western Pacific. The ENSO cycle, both El Niño and La Niña, causes global changes of both temperatures and rainfall. Mechanisms that cause the oscillation remain under study.

Developing countries dependent upon agriculture and fishing, particularly those bordering the Pacific Ocean, are the most affected. In American Spanish, the capitalized term “El Niño” refers to “the boy”, so named because the pool of warm water in the Pacific near South America is often at its warmest around Christmas. “La Niña”, chosen as the ‘opposite’ of El Niño, literally translates to “Spanish for daughter””

“What we are experiencing is typical of an early winter El Niño effect,” said Adam Scaife, the head of Met Office long-range forecasting.

“We expect 2016 to be the warmest year ever, primarily because of climate change but around 25% because of El Niño,” said Scaife, who added that the phenomenon was not linked directly to climate change but made its effects worse.

The 1997–98 El Niño observed by TOPEX/Poseidon. The white areas off the Tropical Western coasts of northern South and all Central America as well as along the Central-eastern equatorial and Southeastern Pacific Ocean indicate the pool of warm water.

Scientists have warned for years that extreme weather would become more common as a result of climate change, but have until recently fought shy of attributing single events to global warming.

El Nino impacts increasingly the global climate and disrupts normal weather patterns, which as a result can lead to intense storms in some places and droughts in others

Average equatorial Pacific temperatures

But in 2015, researchers at Oxford University and the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) calculated that man-made climate change was partly responsible for Storm Desmond’s torrential rain, which devastated parts of Scotland, the Lake District and Northern Ireland. The scientists ran tens of thousands of simulations of the flooding event and found it 40% more likely with climate change.

“We expect 2016 to be the warmest year ever, primarily because of climate change but around 25% because of El Niño,” said Scaife, who added that the phenomenon was not linked directly to climate change but made its effects worse. And, the tendency of temperature increase will accelerate in the decades-to-come.

A warmer climate increases the risk of floods. So far, only a few studies have projected changes in floods on a global scale. None of these studies relied on multiple climate models. Finally, a few global studies have started to estimate the exposure to flooding (population in potential inundation areas) as a proxy of risk, but none of them has estimated it in a warmer future climate. Here we present global flood risk for the end of this century based on the outputs of 11 climate models. A state-of-the-art global river routing model with an inundation scheme6 was employed to compute river discharge and inundation area. An ensemble of projections under a new high-concentration scenario demonstrates a large increase in flood frequency in Southeast Asia, Peninsular India, eastern Africa and the northern half of the Andes, with small uncertainty in the direction of change. In certain areas of the world, however, flood frequency is projected to decrease. Another larger ensemble of projections under four new concentration scenarios reveals that the global exposure to floods would increase depending on the degree of warming, but interannual variability of the exposure may imply the necessity of adaptation before significant warming.

On June 1st, 2016, flooding in Lower Bavaria killed three people in the town of Simbach am Inn. The victims were all found in the same house, he added. Their identities were still unknown. Authorities were still trying to find out whether more people were missing in the area. Another woman was found dead by a stream in the town of Julbach, also a part of Rottal-Inn.

35 liters of rain water fell on one M2 in 4 hours; these apocalyptic rainfalls and cyclones of this magnitude have never been recorded before.

Officials had raised alarm levels in Rottal-Inn on Wednesday, after heavy rains flooded several towns and villages in the area. The town of Triftern, with around 5,000 inhabitants, Simbach am Inn and the Tann area were severely affected by the downpour. Rescue helicopters saved several people from the roofs of their homes.

The Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science (German: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e. V.; abbreviated MPG) is a formally independent non-governmental and non-profit association of German research institutes founded in 1911 as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society[1][3] and renamed the Max Planck Society in 1948 in honor of its former president, theoretical physicist Max Planck. The society is funded by the federal and state governments of Germany as well as other sources.

According to its primary goal Max Planck Society supports fundamental research in the natural, life and social sciences, the arts and humanities in its 83 (as of January 2014) Max Planck Institutes. The society has a total staff of approximately 17,000 permanent employees, including 5,470 scientists, plus around 4,600 non-tenured scientists and guests. Society budget for 2015 was about €1.7 billion.

The Max Planck Institutes focus on excellence in research. The Max Planck Society has a world-leading reputation as a science and technology research organization with 33 Nobel Prizes awarded to their scientists, and are generally regarded as the foremost basic research organization in Europe and the world. In 2013, the Nature Publishing Index placed the Max Planck institutes fifth worldwide in terms of research published in Nature journals (after Harvard, MIT, Stanford and the US NIH). In terms of total research volume (unweighted by citations or impact), the Max Planck Society is only outranked by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Russian Academy of Sciences and Harvard University. The Thomson Reuters-Science Watch website placed the Max Planck Society as the second leading research organization worldwide following Harvard University, in terms of the impact of the produced research over science fields.

The Max Planck Society and its predecessor Kaiser Wilhelm Society hosted several renowned scientists in their fields, including Otto Hahn, Werner Heisenberg, and Albert Einstein, Oppenheimer, to name a few.

Christian Aid insists the world can and must be swiftly changed to one where everyone can live a full life, free from poverty and violence. The NGO works globally for profound change that eradicates the causes of poverty, striving to achieve equality, dignity and freedom for all, regardless of faith or nationality. It states: “We believe in life before death.”

Christian Aid has received a quickly growing recognition (like Green Peace) for its high quality of research and publications, and its balanced analyses of catastrophic developments world-wide.

![]()

Greenpeace is a non-governmental environmental organization with offices in over forty countries and with an international coordinating body in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Founded by Canadian environmental activists in 1971, Greenpeace states its goal is to “ensure the ability of the Earth to nurture life in all its diversity” and focuses its campaigning on worldwide issues such as climate change, deforestation, overfishing, commercial whaling, genetic engineering, and anti-nuclear issues. It uses direct action, lobbying, and research to achieve its goals. The global organization does not accept funding from governments, corporations, or political parties, relying on more than three million individual supporters and foundation grants. Greenpeace has a general consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council and is a founding member of the INGO Accountability Charter; an international non-governmental organization that intends to foster accountability and transparency of non-governmental organizations.

Greenpeace is known for its direct (sometimes daring) actions and has been described as the most visible and trustworthy environmental organization in the world. Greenpeace has raised environmental issues to the public attention, and influenced both the private and the public sector. Greenpeace has also been a source of controversy; its motives and methods (some of the latter being illegal) have received criticism and the organization’s direct actions have sparked legal actions against Greenpeace activists, such as fines and suspended sentences for destroying a test plot of GMO.

MV Esperanza, a former fire-fighter owned by the Russian Navy, was relaunched by Greenpeace in 2002

Supporters of Greenpeace argue, that laws made by dictators and corrupt governments must be broken in order to be able to make a true change. Laws created by dictators and oligarchies will mainly protect their own interests and any change or transparency will be met with fierce resistance and retribution.

Or, what usually happens in countries like more democratic countries like India or the USA, “window dressing” takes place to pacify the public opinion and main stream media.

Billionaire Donald Trump is an excellent example of greed and a politician in denial of global warming. Trump is the nominee for the Republican Party to run for the presidential election in 2016 and argues that 1) cutting greenhouse gasses would be too expensive for the US economy and 2) global warming is an invention of leftist radicals and a small group of run-amok scientists

The above article is collected from materials provided by, among others, the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (Germany), the ChristianAid (UK), Greenpeace (NL); edited by Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.