The Future of Oil and Coal: keep pumping and burning or turning around?

by

* Jaap Tielbeke and ** Robert Gorter

GURU BRAR (India)

June 17, 2020

Oilfield Latshaw Drilling Rig 19 near Stanton, Texas. April 24th (© Tamir Kalifa / The New York Times / HH)

It was a symbolic moment on Wall Street: in mid-April, Netflix’s market value was suddenly higher than that of ExxonMobil. While the streaming service took full advantage of the lockdown, the oil company was hit mercilessly. In a period when half the world was home-bound, people needed a good series more than fuels. The oil price was already struggling due to bickering between Saudi Arabia and Russia, and when they fall in demand from the corona crisis subsequently overcame it, the price of a barrel of crude oil fell below zero for the first time in history. This was not just a dip that is more common in the boom and bust cycles in the oil market, it was an unprecedented shock in an industry that was already under attack. “Coronavirus has exposed just how broken Big Oil is,” reported Technology magazine “Wired.”

Meanwhile, the oil price has recovered somewhat, but a return to “normal” does not seem to be the case for the time being. Market analysts predict a wave of bankruptcies in the oil sector, particularly in the US, where the fracking industry was already struggling to compete with cheap Middle Eastern oil. Shell was forced to cut the dividend for the first time since World War II. For decades, shareholders have been confident that the multinational would, despite all the market fluctuations and turbulent geopolitics, payout a decent profit every year, but now the investor wisdom “never sell Shell” suddenly sounds a lot less convincing. BP plans to cut ten thousand jobs this year, about fifteen percent of the total workforce. “This pandemic reinforces the already existing challenges for the oil sector,” explained CEO Bernard Looney. He even doubted that global oil demand would ever return to pre-crisis levels. Hence, last week BP decided to write off more than $ 13 billion on its assets. The company anticipates that, due to weakened demand and lower prices, some of its oil and gas reserves are likely to remain at the bottom.

Is the end of the fossil industry insight?

The end of “the fossil era” had been announced earlier; late 2015 in Paris, to be precise. When the chairman there hammered the historic agreement between 195 states to limit global warming to well below two degrees, Al Gore was in tears. “This ambitious treaty sends a clear signal to governments, companies, and investors around the world: the transition from an economy fueled by dirty fuels to an economy driven by sustainable growth is undeniably on the way,” said the man who has his famous climate documentary manifests as an unofficial sustainability pope.

The wish was probably the father of the idea because for the time being almost no country fulfills its ambitions, but since then “Paris” has served as an important benchmark. Governments are busy drafting climate plans, and the next international summit, which has been postponed until the end of next year due to the pandemic, needs to tighten up its goals and make the plans more concrete. And if the world is finally serious about climate policy, it will logically have huge consequences for companies that earn their money by pumping up oil and gas.

Those companies are also beginning to realize that they cannot continue on the same footing. Last year, many oil companies presented their own sustainability goals for 2050. The Spanish Repsol set the tone by being the first to declare itself “climate neutral” in thirty years, a goal that was followed by the British BP. The French Total, the Norwegian Equinor, and the Italian ENI also want to reduce their “CO2 intensity”, although the precise roadmap often remains vague. Shell aims to reduce the carbon footprint of its energy products by 65 percent by the middle of this century, although this is not enough if total production grows. “European companies are generally better off than US companies, but they also still have a long way to go,” said Andrew Grant, an analyst with the financial tracker Carbon Tracker.

It is significant, says Grant that almost no group has a strategy to shrink. While that is what must be done in the fossil fuel industry in the coming decades, we want to prevent complete climate disruption. Oil companies would be wise to sort it out by now, he thinks. His advice: pick and sell the low-hanging fruit and let the hard-to-reach fruits hang. Or, as he puts it more technically, “Energy companies should focus on the projects with the lowest costs and highest yields. It is best to repel activities that do not fit that profile, such as the extraction of tar sands. “Financially it does not have to turn out badly at all, he explains. After all, for the time being there is enough money to be made with oil that is cheap and easy to pump up. “After the American oil company, ConocoPhillips embraced such a shrinkage strategy around 2010, it outperformed many competitors. By gradually phasing out your fossil portfolio, you ensure that your revenue model is compatible with the climate goals of the Paris Agreement. I think investors appreciate that certainty. With the proceeds, you can pay a generous dividend to your shareholders – so to say you go into “harvest mode”. It is primarily a psychological challenge for directors, in a world where growth is often seen as the sole survival strategy. ”

The alternative is to transform oneself into a green energy company, but that is easier said than done, Grant acknowledges. Historically, attempts by oil companies to broaden their horizons have not been particularly successful. That is not surprising; companies such as Shell or BP are fully equipped to extract fossil fuels. All the knowledge and skills they have in the house are focused on this. The production of solar or wind energy is a completely different branch of sport. In that respect, it is significant that last year Shell was trumped by Mitsubishi, the Japanese group best known for its cars, in the takeover battle for sustainable energy supplier Eneco. “But on the other hand, there is the example of the Danish oil company that has merged into an energy company that is now investing heavily in offshore wind energy,” says Grant. “Their shares have risen sharply since then. The problem is that most oil companies take some sort of middle ground: they invest a small part of their capital in clean energy but continue to expand their fossil fuel activities. Sustainability is not going well. ”

“We have to realize that we cannot continue to use fuels and raw materials as we have done for the past quarter-century.” In 1973, the Dutch Prime Minister Joop den Uyl addressed the population directly. The world is struggling with an oil crisis and in the Netherlands, petrol is on the receipt. Den Uyl looks worried, his tone is serious. Although the acute crisis is caused by production restrictions in Arab countries, he seems to see this as a harbinger of a new era. A year earlier, the Club of Rome in the famous Borders to Growth report warned of upcoming commodity scarcity. For example, there would simply be too little oil in the soil to meet the ever-growing demand, and that impending shortage would push fuel prices up. In Den Uyl’s speech, that fear of peak oil resonates. “Today’s crisis is a shocking expression that there was already an energy shortage in the world,” said the prime minister. “Seen in this way, the world before the oil crisis does not return.”

His fear was unfounded. In the past thirty years, the world has only started to use more fossil fuels, because there appeared to be an abundance of reserves in the soil. We can dig up enough coal to meet our energy needs for the next hundred years. With the now known oil and gas reserves, we can still go on for about fifty years. So the problem is rather too much fossil fuel, because in Den Uyl’s time global warming may not have been at the top of the agenda, but we now know that burning oil, coal and natural gas releases greenhouse gases that threaten the climate to disrupt.

Still, the fossil fuel industry spends billions on the search for undiscovered oil fields or gas bubbles, invests heavily in technological innovation, and constructs new pipelines. While no “gray” energy infrastructure should be added if we want to achieve the Paris climate goals, a scientific study in Nature concluded last year. If all existing and planned coal-fired power stations and oil wells were to continue to operate for their full lifespan, we would already exceed our ‘carbon budget’.

His fear was unfounded. In the past thirty years, the world has only started to use more fossil fuels, because there appeared to be an abundance of reserves in the soil. We can dig up enough coal to meet our energy needs for the next hundred years. With the now known oil and gas reserves, we can still go on for about fifty years. So the problem is rather too much fossil fuel, because in Den Uyl’s time global warming may not have been at the top of the agenda, but we now know that burning oil, coal and natural gas releases greenhouse gases that threaten the climate to disrupt.

Still, the fossil fuel industry spends billions on the search for undiscovered oil fields or gas bubbles, invests heavily in technological innovation, and constructs new pipelines. While no “gray” energy infrastructure should be added if we want to achieve the Paris climate goals, a scientific study in Nature concluded last year. If all existing and planned coal-fired power stations and oil wells were to continue to operate for their full lifespan, we would already exceed our ‘carbon budget’.

“It is a delusion that we can solve climate change by calling on investors to withdraw their money from the fossil fuel industry.”

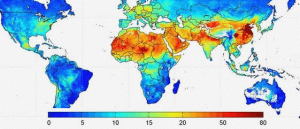

Although almost all countries have signed the Paris Convention, their actions tell a different story. Every year, the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) issues an Emissions Gap Report, critically reviewing states’ climate plans. The conclusions are worrying. If we still have a reasonable chance of limiting global warming to one and a half degrees, CO2 emissions must be reduced to 25 gigatons by 2030. But with current policies, we’re on course for 56 gigatons, which would mean global warming by more than three degrees. So there is a frightening gap between climate science and political reality.

That gap will only widen if you consider the plans for the extraction of fossil fuels. “Negotiations at the United Nations are only about emissions, no one holds countries responsible for the oil, coal, and gas extracted from their soil in their territory,” said Cleo Verkuijl, a researcher at the Stockholm Environmental Institute (SEI). That is why SEI, together with four other research institutes and UNEP, decided to investigate the ‘production gap’ in addition to the Emission Gap Report. The conclusions of that report are even more worrying: if we burn all the fossil fuels that countries think they can get out of the ground, we will emit even more than 56 gigatons. “There is a huge mismatch in almost every country,” says Verkuijl, “even in countries that are emerging as climate leaders, such as Norway, Canada, or the United Kingdom.”

Because countries are only judged by their emission figures, they can rhyme that they want to reduce emissions while continuing to extract fossil fuels. After all, oil, coal, and gas can be exported and the responsibility for the greenhouse gases does not lie with the producer but with the final consumer. But if every country reasons this way, the world will soon be faced with a huge surplus of fossil fuels. “Then two more scenarios are possible,” says Verkuijl. “Whether those fuels are consumed because otherwise it is wasted money. But that would be disastrous for the climate. Or we take the climate goals as seriously as we should and that means we can’t use much of that oil, coal, and gas. That would have enormous social and economic consequences. ”

She continues: “In that respect, you can see the social consequences of the corona crisis as a warning. It offers a glimpse into what happens when all kinds of drastic measures suddenly have to be taken. The economy is in trouble, jobs are being lost, it is causing fear, uncertainty, and grief to a lot of people. That is what we are heading for again if we don’t take action. We can learn from this how not to do it. ”

Construction of the Russian Gazprom pipeline in Germany (2019) (© Paul Langrock / Laif / HH)

Every working day, Jim Cramer, a former hedge fund manager, provides investment advice on his TV show Mad Money. “My mission is simple,” he says in the exciting introduction, “make sure you earn money!” Early this year, he was asked about his predictions for the fossil fuel industry. The course of Exxon and Chevron was once again in the red. “I’m done with fossil fuels,” said Cramer without further ado. “They’re done.” An approaching lockdown wasn’t even his biggest fear. The oil companies performed quite well, but according to Cramer, the sector had had its longest time. “The world has changed,” he said. “Young people don’t want to own these stocks anymore, even if they still offer such a great dividend.” He saw more and more investors take their money out of the industry because they see that fossil energy companies have no future-proof earnings model and have ended up in the same damn corner like the tobacco industry. “The death bells have sounded,” Cramer concluded.

If the dying process is not properly supervised, the impending death of the fossil fuel industry can cause major shock waves in the financial markets, Andrew Grant knows. His employer, the Carbon Tracker, was the first to prominently place the uncertain future of the fossil fuel industry on the agenda in 2011, with a report on the “carbon bubble” – the carbon bubble. That report was primarily intended as a warning to investors. Beware: investing in the fossil fuel industry is not only morally questionable, but it is also financially risky. Because when investors soon realize that a large part of the fossil reserves must remain in the ground to prevent a climate disaster, those assets will lose their value, and the stock market value of oil companies will collapse. “Ten years ago, no one thought about the financial risks,” said Grant. “The” carbon bubble “is now a well-established concept among investors. The huge price swings during the corona crisis will only make investors more nervous. ”

How quickly the tide can turn proves the coal sector. Global consumption of the most polluting fuel seems to have finally peaked. “When demand fell by a few percents, many American coal producers went bankrupt,” said Grant. And if governments want to close the production gap, such a scenario is also inevitable for the oil industry. “Investors are already responding to that,” says Grant. Despite the record-high cash flows in 2018, the price of their shares barely rose. Or are the reports of the death of the fossil fuel industry somewhat exaggerated? The most optimistic projections assume that global oil consumption will return to pre-crisis levels by the end of the year. Now that demand is picking up again and the petroleum price is climbing, Saudi Arabia is looking to the future with confidence again. The corona crisis may have caused an unprecedented deep trough, but if we have to believe the oil sheiks, the way up has already started.

“The end of Big Oil is far from insight,” says British economist Dieter Helm. “It is a delusion that we can solve climate change by calling on investors to withdraw their money from the fossil fuel industry. Many of those “divestment” campaigns are targeting private oil companies such as Shell or Exxon, but 90 percent of the oil market is already owned by state-owned companies and they are completely immune to that type of action. ”He also doesn’t believe that shareholders are among the impressed with the carbon bubble warnings.” That is a purely theoretical danger that will manifest itself in thirty years at most. I don’t know of any asset manager who looks more than five years ahead. ”

Still, Helm published a book called Burn Out: The Endgame for Fossil Fuels in 2017. Because although the world is far from getting rid of the addiction to oil, coal, and gas, the heyday of the fossil fuel industry is irrevocably over. In his book, he identifies three “predictable surprises” that will eventually kill the sector.

Every working day, Jim Cramer, a former hedge fund manager, provides investment advice on his TV show Mad Money. “My mission is simple,” he says in the exciting introduction, “make sure you earn money!” Early this year, he was asked about his predictions for the fossil fuel industry. The course of Exxon and Chevron was once again in the red. “I’m done with fossil fuels,” said Cramer without further ado. “They’re done.” An approaching lockdown wasn’t even his biggest fear. The oil companies performed quite well, but according to Cramer, the sector had had its longest time. “The world has changed,” he said. “Young people don’t want to own these stocks anymore, even if they still offer such a great dividend.” He saw more and more investors take their money out of the industry because they see that fossil energy companies have no future-proof earnings model and have ended up in the same damn corner like the tobacco industry. “The death bells have sounded,” Cramer concluded.

If the dying process is not properly supervised, the impending death of the fossil fuel industry can cause major shock waves in the financial markets, Andrew Grant knows. His employer, the Carbon Tracker, was the first to prominently place the uncertain future of the fossil fuel industry on the agenda in 2011, with a report on the “carbon bubble” – the carbon bubble. That report was primarily intended as a warning to investors. Beware: investing in the fossil fuel industry is not only morally questionable, but it is also financially risky. Because when investors soon realize that a large part of the fossil reserves must remain in the ground to prevent a climate disaster, those assets will lose their value, and the stock market value of oil companies will collapse. “Ten years ago, no one thought about the financial risks,” said Grant. “The” carbon bubble “is now a well-established concept among investors. The huge price swings during the corona crisis will only make investors more nervous. ”

How quickly the tide can turn proves the coal sector. Global consumption of the most polluting fuel seems to have finally peaked. “When demand fell by a few percents, many American coal producers went bankrupt,” said Grant. And if governments want to close the production gap, such a scenario is also inevitable for the oil industry. “Investors are already responding to that,” says Grant. Despite the record-high cash flows in 2018, the price of their shares barely rose. Or are the reports of the death of the fossil fuel industry somewhat exaggerated? The most optimistic projections assume that global oil consumption will return to pre-crisis levels by the end of the year. Now that demand is picking up again and the petroleum price is climbing, Saudi Arabia is looking to the future with confidence again. The corona crisis may have caused an unprecedented deep trough, but if we have to believe the oil sheiks, the way up has already started.

“The end of Big Oil is far from insight,” says British economist Dieter Helm. “It is a delusion that we can solve climate change by calling on investors to withdraw their money from the fossil fuel industry. Many of those “divestment” campaigns are targeting private oil companies such as Shell or Exxon, but 90 percent of the oil market is already owned by state-owned companies and they are completely immune to that type of action. ”He also doesn’t believe that shareholders are among the impressed with the carbon bubble warnings. “That is a purely theoretical danger that will manifest itself in thirty years at most. I don’t know of any asset manager who looks more than five years ahead. ”

Still, Helm published a book called Burn Out: The Endgame for Fossil Fuels in 2017. Because although the world is far from getting rid of the addiction to oil, coal, and gas, the heyday of the fossil fuel industry is irrevocably over. In his book, he identifies three “predictable surprises” that will eventually kill the sector.

- 1 pm in New Delhi, India: severe air pollution (2019)

The first predictable surprise is the long-term steady decline in oil prices. In 2012, a barrel of oil cost around a hundred dollars, and prices were only expected to rise until the petroleum market collapsed completely in 2014. That came as no surprise to Helm. The high prices at the beginning of the century were the exception rather than the rule. Certainly, now that the demand for fossil fuels has weakened due to the energy transition, it is likely that amounts of eighty dollars a barrel are a thing of the past. “A price dip was coming anyway, the decline had already started before the world went into lockdown,” said Helm in a video call from London. “The corona crisis only intensified this.”

“If a fish species is about to die out, we don’t say,” Gosh, we should eat less of that. “No; we set quotas for fishermen.”

The second predictable surprise is that climate policy is becoming increasingly strict. As the effects of the warming earth become more tangible, politicians are beginning to see that something needs to be done quickly. “And the survival of oil, coal and gas companies simply cannot be reconciled with combating climate change,” Helm writes in his book. That insight is not new, yet “no one has a convincing post-fossil strategy.”

Helm does not believe that we already have all the technology in house to solve the climate crisis, as is sometimes claimed in green circles. A great deal of innovation is still needed before we can capture the fossil energy that remains in the soil with renewable sources. The good news is that this development is already in full swing, particularly in the field of solar energy. That is the third predictable surprise: we are moving towards an “electric future” in which there is no place for oil and coal.

But that future will not come automatically, Helm emphasizes. Nor does the corona crisis automatically bring such a future closer. A low oil price can hinder the energy transition because it becomes more difficult for clean sources to compete with fossil energy. “That’s why I don’t understand why the renewable energy industry likes to brag so much that it can do it without subsidies,” says Helm. “It would be great, but it is not yet. Renewable energy sources need protection from the government. ”

That was also the message from Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency (IEA), who urged governments after the corona crash not to lose sight of the environment. If governments now choose the easy route, by blindly helping the fossil fuel industry and keeping the old economy going, the climate goals will go even further out of sight. At the end of May, the IEA concluded in its World Energy Investment Analysis that investments in renewable energy had fallen considerably. “This puts us at risk of being delayed in the much-needed transition to a more resilient and sustainable energy system,” said Birol. But if politicians make the right decisions, it can ensure that the energy transition is accelerating.

To provide policymakers with tools, the Oil Change International research group has compiled a list of do-and-don’ts. In any case, in the wake of the corona crisis, politicians should resist the temptation to bail out polluting industries or relax, temporarily or otherwise, environmental legislation. Another danger is that during crisis management governments postpone their climate plans. “Now is the time to ensure that the response to this crisis brings climate goals closer, rather than pushing them further away,” the researchers write.

People on their way to work on an “average” day in New Delhi, India

The first logical step is to reduce subsidies to the fossil industry. Last year, the International Monetary Fund calculated that more than four trillion (four thousand billion!) Euros of disguised state aid go to the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels every year. For example, the costs of air pollution are passed on to society as a whole and governments keep energy prices artificially low with subsidies. Admittedly, the IMF uses a rather broad and controversial definition of subsidies, because those who look through such glasses will hardly find an industry that does not get any support from politicians. But such a broad view does provide insight into how governments with financial incentives maintain the fossil economy. And even if we only look at direct subsidies, this is an amount of four hundred billion dollars, the IEA calculated in 2018. If governments that redirect subsidies towards clean sources, that stimulates the energy transition.

According to Oil Change International, this is an excellent time to introduce a strong CO2 tax. Because oil is so cheap now, an extra charge will not directly lead to extremely high energy prices. That is also the recommendation of the liberal weekly The Economist, which recently called on governments to seize the corona crisis to also bring down the climate curve: “Low energy prices make it easier to cut fossil fuel subsidies and tax Enter CO2. (…) A small boost from a carbon tax could provide a decisive advantage for renewable energy, which would also make its permanent roll-out cheaper. There may never have been a time when a price on CO2 could have such a big effect so quickly. ”

Oil Change International’s report goes one step further. Because one of the most important conclusions is that the market can no longer solve this problem, even if governments gently steer the market through subsidies or taxes. Until now, climate policy has mainly focused on the demand side. But it is time that the supply side was also looked at, according to Andrew Grant of Carbon Tracker. “We find that perfectly normal in other sectors. When a fish species is in danger of extinction, we don’t say, “Gosh, maybe we should eat less of that.” No, we set quotas for fishermen. Production is being cut short – that is also what is needed in the fossil industry. ”

There are already countries that are taking steps in that direction. For example, there is a climate law in the Spanish parliament that would prohibit the search for new fossil resources. New Zealand previously announced that it would no longer issue permits for deep-sea drilling offshore. And if it is up to President Macron, oil and gas may no longer be extracted on French territory from 2040. California is also considering halting the construction of new oil wells. Such policy is urgently needed, says SEI researcher Cleo Verkuijl, because every new drilling platform or new pipeline that is now being added creates a “path dependency” that makes the transition to a sustainable economy even more difficult. And the longer we stay on the fossil path, the faster the Earth will warm up.

To keep the planet livable for generations to come, the fossil industry will have to shrink considerably within one generation. It is the task of governments to ensure that this proceeds in an orderly manner, says Verkuijl. She insists on the importance of a “fair transition”, highlighting the many workers, regions, and communities affected by the change. “They should not be left to fend for themselves. It is important to share costs fairly. “Internationally, wealthy countries that have benefited from fossil fuels for the longest time should take the lead in moving to a cleaner economy.

Climate activists hoping that the corona crisis would be the final blow to a dying industry are likely to be disappointed. It takes more than a temporary shock to break our dependence on oil, coal, and gas. Investors, consumers, directors – they will only really get going when politicians make it clear that the end of the fossil era has arrived; and as long as oil companies receive rescue packages as soon as they get into trouble that point has not yet been reached.

But it is abundantly clear that the corona crisis has further shaken this industry, whose limited shelf life was evident long before the pandemic. While their lobbyists still manage to get support from governments, they may be the last throes of a dying industry. If oil companies have to cut costs, they may also have to cut back on advocacy, Andrew Grant thinks. “Their political power is waning and social pressure is increasing every year.” To paraphrase Den Uyl: in this sense, the world from before the corona crisis does not return.

* Jaap Tielbeke (1989) has been working on the editorial staff of the Dutch newspaper De Groene Amsterdammer since 2015. Before that, he studied International Relations in Groningen and Philosophy in Antwerp and Nijmegen. For De Groene, he mainly writes about climate change, social movements, and democratic renewal. He has also published, among other things, on the ideology of philanthropic capitalists and the degeneration of WikiLeaks.

** Robert W. Gorter, MD, PhD, studied medicine in addition to philosophy and ecology at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Gorter worked for Amnesty International and conducted multiple missions to study and document human rights violations in countries such as Argentina, Russia, and Romania. According to Dr. Gorter is pollution an example of ignoring human rights and another proof that 1% exploits the other 99% at all costs.

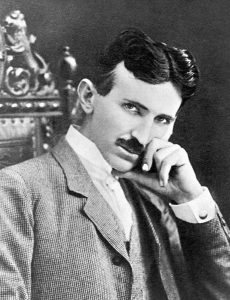

Those who own the PetroDollar will do everything in their power to torpedo what scientists like Nikola Tesla showed as an energy source and away from fossil fuels, such as oil and coal; and nuclear energy.

Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) was a Serbian-American inventor, electrical engineer, mechanical engineer, and futurist best known for his contributions to the design of the modern alternating current (AC) power grid.

Born and raised in the Austrian Empire, Tesla studied engineering and physics in the 1870s without graduating and gained practical experience in telephony and Continental Edison in the new electricity industry in the early 1880s. In 1884, he emigrated to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen. He worked for a short time at the Edison Machine Works in New York City before hitting on his own. With the help of partners to finance and market his ideas, Tesla set up laboratories and companies in New York to develop a range of electrical and mechanical equipment. His alternating current (AC) induction motor and related multiphase AC patents, licensed by Westinghouse Electric in 1888, earned him a significant sum and became the cornerstone of the polyphase system that that company eventually marketed.

Second banquet meeting of the Institute of Radio Engineers, April 23, 1915. Tesla is seen in the center.

To develop inventions that he could patent and market, Tesla conducted a series of experiments involving mechanical oscillators/generators, electric discharge tubes, and early X-ray imaging. He also built a wirelessly controlled boat, one of the first-ever to be exhibited. Known as an inventor, Tesla demonstrated his achievements to celebrities and wealthy clients in his laboratory and was known for his showmanship at public lectures. Throughout the 1890s, Tesla continued his ideas for wireless lighting and global wireless power distribution in his high-voltage and high-frequency power experiments in New York and Colorado Springs. In 1893, he made statements about the possibility of wireless communication with his devices. Tesla tried to put these ideas to practical use in his unfinished Wardenclyffe Tower project, intercontinental wireless communications and power transmitter but ran out of funding before he could complete it.

After Wardenclyffe, Tesla experimented with varying success in a series of inventions in the 1910s and 1920s. After spending most of his money, Tesla lived in a range of New York hotels, leaving unpaid bills. He died in New York City in January 1943. Tesla’s work became relatively unknown after his death, until 1960 when the General Conference on Weights and Measures named the SI unit of magnetic flux density the tesla in his honor. Since the 1990s, Tesla has become popular again because his inventions could be the answer to withdraw from fossil energy.

natural resources like crude oil are limited. but still we want and used woth recklessly.

petroleum companies create their monarch for , with the control of existenting government.

this is the bad side of pressure groups or parallel government, who run the world actually.