What have Billionaires and Dictators in common? They want the mass media, as who owns the mass media owns the public opinion

by

Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.

October 26th , 2020

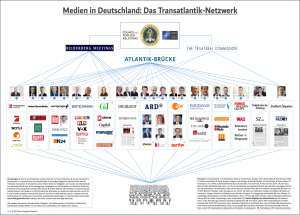

Note on the interpretation of the organogram

The infographic is neither an »organizational chart« nor a »conspiracy«, but a publicly documented, political-journalistic network. The top level (CFR, NSC, NATO) defines the transatlantic geostrategy, which is generally mapped by the listed media.

Media researcher Noam Chomsky explained this in a 1997 essay as follows:

»The crucial point is: These journalists wouldn’t be there if they hadn’t proven long ago that nobody has to tell them what to write – because they’ll write the“ right thing ”anyway. () In other words: these journalists went through a socialization process. “

About the fight for opinion

The reception of the present dissertation, which was published by Herbert von Halem Verlag in February 2013, can be roughly divided into two chapters:

The first takes place in front of this panel number from the ZDF satirical program Die Anstalt on April 29, 2014 (see Die Anstalt 2014), which was based on the network analysis from this book, and the second afterwards. Before the sketch, which reached more than two million TV viewers that evening and then went viral through the social networks, the criticized journalists had ignored the book, after the sketch they could no longer do it. Before the sketch, the study received a neutral to benevolent reception in the communication science community, after the sketch it drew massive criticism, especially from conservative heavyweights in the field. With Pierre Bourdieu’s scientific III sociological terms (cf. Wiedemann / Meyen 2013) one could also outline the discussion about opinion power among scientists as follows:

In the beginning, actors on the fringes or outside the communication science field (scientists with little symbolic capital and / or from neighboring disciplines) received the work almost entirely positively. But when the work became powerful in the public discourse and fueled the lie press and mainstream media debate that started in 2014, it was fought by actors with high, symbolic capital from the center of the field. After the institution it was about something.

Let’s start with the reception of the book in the mass media and in the journalism industry. Immediately after publication, an interview in the online magazine Telepolis brought the book a lot of attention and me a series of lecture requests, invitations to panel discussions and interviews in public radio stations (Deutschlandfunk, WDR, RBB). In Switzerland, the radio station SRF 2 Kultur selected the dissertation for the non-fiction book of March 2013, and by the end of the year reviews appeared in four German daily newspapers: the taz, the Junge Welt, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the Süddeutsche Zeitung (sources in Krüger 2019). Even the last two were friendly and obviously not guided by the interests of the respective foreign policy editors. The criticized journalists initially kept a low profile in phase 1. In phase 2, after the institution, the level of arousal rose sharply, both among the criticized journalists and in public: Josef Joffe and Jochen Bittner von der Zeit took legal action against the institution (and ultimately lost before the Federal Court of Justice), Stefan Kornelius von der Süddeutsche defended himself against the allegations in the NDR media magazine Zapp. Meanwhile, the federal chairman of the German Association of Journalists spoke out against lobbying by journalists, and even the vice-editor-in-chief of the time demanded in a pamphlet that journalists from transatlantic organizations should say goodbye because the foreign policy debate in Germany has a strange American accent have (details in Krüger 2019; Krüger 2016: 96-101).

The two phases can also be seen in the scientific discussion about the doctoral thesis. In the first time after publication, the work was initially discussed by scientists from related disciplines: from political science, sociology and (peace) psychology. On the portal for political science, Nils Hesse, who has a doctorate in political science, economics and business administration and at the time was a consultant at the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, reviewed:

»He [Krüger] clearly shows how the argumentation patterns within the elite milieu on foreign and security issues are similar. The results indicate that not only individual journalists, but the leading media as a whole, at least in the subject area examined, have a strong tendency to merely depict discourses of the elite and to ignore or de-legitimize divergent arguments. This observed questionable handling of the power of opinion is too seldom the subject of methodologically sound, scientific analyzes. This work is all the more remarkable. It is an important contribution to an open and factual discussion about independence in German editorial offices beyond conspiracy theories «(Hesse 2013).

Thomas Meyer, professor emeritus of political science at TU Dortmund University and editor-in-chief of the political-cultural journal Neue Gesellschaft / Frankfurter Hefte, wove the results of the study into his media-critical book “Die Unbelangbaren” with a similar flick of the tongue.

He praised that the author “reveals, on the basis of meticulous detailed work, how closely authoritative representatives of leading media […] in the field of foreign and security policy are linked with political advisors and current or former top politicians in the context of think tanks, academies and discussion forums” ( Meyer 2015: 108f.). Karin Urich, who has a doctorate in contemporary history and editor of Mannheimer Morgen, praised the dissertation with a detailed description of the content and stated that the author had proceeded “cautiously” (Urich 2013: 129, 132).

In the interdisciplinary quarterly journal Wissenschaft & Frieden, which is devoted to peace research, peace movement and peace politics, the book was reviewed by Gert Sommer, an emeritus professor of psychology at the University of Marburg and long-time chairman of the Forum Friedenspsychologie. After a detailed

Explaining the content, he judged:

»For the critical media consumer, Krüger’s results are hardly astonishing. Peace movements and peace scientists know that there are alternative sources of information (including ialana.de, imi.de, friedenskooperative.de, ag-friedensforschung.de, ippnw.org). However, the book proves empirically that the highly praised quality media in Western democracies do not fulfill their task of reporting critically and neutrally, or only to a very limited extent. […] Krüger’s book is very recommendable «(Summer 2014: 64).

Also not surprising in view of the results – albeit from a less peace-loving and left-wing position – Boris Holzer, Professor of General Sociology and Macrosociology at the University of Konstanz, appeared in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. He followed the train of thought of the work and then criticized two points:

Firstly, it remains open whether there is a causality between personal network and personal opinion (which is also said in the book on pp. 220f. And p. 258).

Secondly, the expectations of journalism are “sometimes a bit high and therefore perhaps particularly susceptible to disappointment.

If you assign the journalist the ›professional role of the neutral observer‹, basically expect more from the reporting than reflect the diversity of opinion of the political elite, and this from a ›functionally higher point of view‹, then the disappointment is basically programmed. […] In this case, one could therefore assume that the normative claims mentioned are not a good social science theory ”(Holzer 2013).

Claims such as »plurality or even neutrality« would »not be redeemed by the individual journalist or even the individual report […], but – if at all – by the system of the mass media as a whole. Regardless of the detailed revealing results of Krüger’s study, one does not necessarily have to share the fear that public opinion as a whole would be controlled by political and economic elites «(ibid.).

It is interesting that Holzer, as a proven network researcher, did not exercise any methodological criticism – that came later, after the institution, from communication science.

But initially the (published) responses from my own subject were positive to ambivalent. In August 2013, a blog entry in the European Journalism Observatory reported the content of the work together with that of another study (cf. Grass 2013). At the beginning of 2014, in addition to journalism, the most important organ of German-language communication studies, Media & Communication Studies published a review by Christian Nuernbergk, then a research assistant (post-doc) at the chair of Christoph Neuberger at LMU Munich and temporary academic adviser. The reviewer said: “The overall procedure is described in a comprehensible manner. The discussion of the diverse results, which suggest a one-sided reporting by the four journalists examined in detail, is being conducted from different sides «(Nuernbergk 2014: 108). With regard to the theoretical approaches imported from the USA, it was said: “This critical expansion makes the book exciting” (ibid.). Although there would have been “further points of contact” in terms of theoretical approaches and the state of research, Nuernbergk’s verdict was summarized:

“In view of the (elite) discourse examined here, Uwe Krüger’s work provides a critical anchor point that is recommended for journalists, students and scientists alike.”

A little later another review appeared in Communicatio Socialis – magazine for media ethics and communication in church and society. Petra Hemmelmann, then a lecturer for special tasks at the journalism chair at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, wrote:

»Overall, Krüger provides diligently researched, detailed and useful information on the interdependence of alpha journalists with political and economic networks. However, there is no reason to fear that these journalists will create a power of opinion in the sense of a monopoly of opinion – and Krüger cannot prove that in this work either «(Hemmelmann 2014: 500).

Otherwise she mainly criticized points that Boris Holzer had already mentioned in the FAZ, and that with an amazingly similar choice of words.

In the meantime, the offshoots of the Anstalt sketch shook the journalist industry and larger parts of the public, and in September 2014 the book Kopp-Verlag published the book Bought Journalists – How Politicians, Secret Services and High Finance in Germany Direct Mass Media by the former FAZ editor Udo Ulfkotte (2014). Ulfkotte invoked opinion power in many places, sharpening and generalizing his findings.

His book, which the media critic Stefan Niggemeier after a fact check as “full of exaggerations, distortions and untruths”

(Niggemeier 2014), soon appeared on the Spiegel bestseller list and sold 120,000 times in the first six months after publication alone (cf. Fleischhauer 2015: 98).

In connection with the growing media criticism and the increasingly publicly voiced suspicion of conspiracy, the industry magazine Medium Magazin published a cover story in November 2014 on the subject of »You’re all lying! – Media caught in the credibility trap «. It contained statements and interviews with reporters and high-ranking editors on the subject of a “crisis of confidence” as well as a review of the power of opinion by Christoph Neuberger, Professor of Communication Studies and Director of the Institute for Communication Studies and Media Research at LMU Munich. With reference to Die Anstalt and Ulfkotte’s book, Neuberger introduced that the dissertation had become “the focal point of the dispute” (Neuberger 2014a: 24).

Then he cited a number of points of criticism of the methodical design, of the underlying premises and assumptions as well as of the interpretations, opinions and demands that I represent. Referring to the points would go beyond the scope of this preface; they and my answers can be found in a replica at the European Journalism Observatory (cf. Krüger 2014). The debate continued with a long duplicate by Neuberger (2014b) in which new points of criticism were raised; It was emphasized that the “review of the dissertation […] had revealed a large number of deficiencies” and that in view of the public attention it had received, an “academic discussion about it was urgently required”. My doctoral supervisor Michael Haller, emeritus professor of journalism at the University of Leipzig and scientific director of the European Institute for Journalism and Communication Research (previously the Institute for Practical Journalism and Communication Research) in Leipzig answered the duplicate. Many method deficiencies listed by Neuberger are “subtle insofar as they do not limit the mentioned validity of the findings or do not significantly limit them.” Haller wrote that “a clever young researcher is being deliberately discredited,” and Neuberger’s criticism “does not pursue enlightenment, but rather the goal of turning the discourse about the political ’embedded’ of so-called alpha journalists:

By badly doing Krüger’s study, the alpha journalists […] are virtually washed clean of the suspicion of elite cohesion «(Haller 2015). Finally, Stephan Ruß-Mohl, (now emeritus) professor of communication science at the University of Lugano, summarized the debate in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung critically: »The harsh condemnation goes to Krüger’s tentative, cautious attempts, the power of opinion of the leading media and the interdependencies of the Finding alpha journalists with the ruling elite is simply over ”(Russ-Mohl 2015). Quasi-incidentally, the debate also revealed that Neuberger is on the advisory board of the SZ-Studienstiftung together with the foreign affairs department head of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Stefan Kornelius, and that the latter drew attention to the book and that Neuberger’s criticism appeared in the magazine whose Kornelius was the first editor-in-chief once (Herkel 2014; Neuberger 2014b; Haller 2015). This does not devalue Neuberger’s arguments per se, but shows that the basic topic of the dissertation, namely the personal networks of speakers in the public arena, is definitely relevant for the analysis and classification of media-mediated communication.

In autumn 2015, Hans Mathias Kepplinger, emeritus professor for empirical communication research at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, published another harsh criticism of the power of opinion in journalism. Some are “well-founded” (the selection of organizations for the network analysis), “formally impressive” (the graphical representations of the ego networks) and “careful” (the frame analysis for the expanded security concept) (Kepplinger 2015: 363), at the same time “content but questionable for theoretical and methodological reasons” (the above-mentioned frame analysis) or only “decorative accessories” (the network graphics) (ibid.). The reader gets a »grossly misleading impression« from the theoretical and methodological innovations, among others. for the definition and identification of leading media and for the co-orientation of journalists. The statements on Noelle-Neumann’s theory of public opinion […] «(ibid .: 362) are downright grotesque. Kepplinger missed a “democratic theoretical foundation – for example on the basis of the classic texts of the Federalists, By Toqueville [sic!] Or von Lippmann” and also “Fraenkel’s fundamental remarks on the representation of interests and will formation in pluralistic societies” (ibid.). In the frame analysis “two variables are mixed up” (ibid .: 363), namely “(a) the membership of journalists in the networks with (b) the editorial lines of their own and other media” – a criticism to which I respond answered in an interview with Michael Walter (2015) on the social science internet portal Soziopolis have. Kepplinger stated ignorance and omission in further points: “He does not know the theoretical background of research into the left-right spectrum […]” (ibid .: 364). “Nor does he discuss the necessity and legitimacy of such connections [of journalists to the organizations]. Instead, he discredits them without concrete evidence for his far-reaching judgments as hardly compatible with u. a. the press code “(ibid .: 363). “These deficiencies are serious because the author uses his insufficiently reflected data to make serious general, but empirically unproven suspicions against politics and the media” (ibid .: 364).

While Michael Meyen, professor of communication science at the LMU Munich, stated in the (positive) review of a left interview tape on media criticism that »Uwe Krüger […] seems to be one of the most important fixed points for media criticism in Germany« (Meyen 2017 ), the scientific heavyweights Neuberger and Kepplinger obviously wanted to prevent this. Your veto votes are unmistakable: »Transparency, systematics and completeness are important principles of empirical research. They were disregarded at several points in the work «, wrote Neuberger (2014a: 24),» [w] he Krüger describes as a frame analysis, in no way does justice to the demands of such an examination «(ibid .: 25) and» [i] n Krüger’s dissertation, the relationship between journalism, elites and the population is presented as a web of power and manipulation relationships. There is a lack of a deeper understanding of how the public should function in a democracy and also – despite some compromises – functions (ibid.) «. In his review Kepplinger (2015: 364) judged the author’s cognitive abilities in a similarly damning way:

»For the reasons mentioned, the book provides – despite a number of remarkable empirical findings, the theoretical and practical significance of which the author is in part does not recognize, partly does not understand and partly overinterpreted – no scientifically founded and practically relevant analysis of the power relations between the political and media elites. ”

In plain language: Opinion power is not a science, and the less well-off should better stay outside – especially when they are on a political crusade:

“The conditions, possibilities, necessities and types of relationships between politicians and journalists are not even remotely reflected. Instead, the book contains political polemics against i.a. the affirmative reporting of important media about a security policy concept. You can find that, including the reporting about it, wrong or right, which is not based on scientific knowledge, but on political attitudes «

Neuberger (2014a: 25) made the same argument of alleged political bias:

»Public statements by Krüger on the debate on security policy in Germany [probably referring to memories of the peace norm in the Basic Law – UK] confirm that he is not in the role of a neutral, impartial scientist, but takes a position on the matter himself. This corroborates the suspicion that with his dissertation he wanted one thing above all: to make an opinion. “

Even if a historicizing analysis is difficult in one’s own right: In my opinion, the polarized and sharply conducted debate about the power of opinion, i.e. about the quality of the work and the validity and scope of its results, is also a struggle for the power of opinion in a larger social framework (How independent and credible are the media?) And not least to be understood in the smaller context of German-language communication studies, in a politically heated time.

“If you follow Bourdieu […], then the scientific field is a social world with hierarchies and constraints, structured by the fundamental opposition between ruling and controlled actors.

[…] According to Bourdieu, the power pole of the field plays a special role, both in terms of content and on an institutional level, because it defines the habitus and the capital for a successful positioning in the field. At the power pole of the scientific field, it is defined which questions, theoretical approaches and methods are considered legitimate […] or which research areas, which networks and which publication sites pay off for a career «

(Wiedemann / Meyen 2016: 6).

The struggle for “power of opinion” also revolved around how media-critical and fundamentally oppositional communication science can be. Is it allowed to operate with political economy á la Herman and Chomsky (2002) as a basis or to carry out ›Power Structure Research‹ in the tradition of C. Wright Mills (1956)? Can she attack individual alpha journalists and accuse them of propaganda? Can it be suspected of excessive horizontal elite integration per se

ask and may it ask whether the actually existing liberal-democratic public functions at all?

Holger Böning, as a media historian and professor of modern German literature and the history of the German press at the Institute for German Press Research at the University of Bremen, also a communication scientist on the edge of the field, recently said in an interview, referring to his own benevolent collective review and a. to power of opinion:

»I would not recommend any young scientist to publish a literature report like the one I did downright fake news and the lying press (cf. Böning 2018). If you do that with this tenor, it will be difficult. For example, I watch Uwe Krüger very closely.

What will become of him after these books (cf. Krüger 2013, 2016) (Meyen 2019)? In any case, it is noticeable that these books – opinion power and popular science

Successor Mainstream from C.H. Beck (cf. Krüger 2016) – hardly find any expression in the ongoing specialist discourse. Significantly, they are not even mentioned in statements about the lying press debate and lists of important books from the debate (see Blöbaum 2018: 607). The sales success – opinion power has sold very well for a dissertation with over 7,000 copies, mainstream in the same order of magnitude – and the perception in the media-critical public is offset by non-perception on the part of the subject: the power pole of the field does not want to pursue the questions raised in opinion power; he does not accept the discourse framework set up here, its problem definitions and perspectives.

So the question is not only what will become of the author of these lines in the course of the internal struggles over topics and interpretations, but also of those questions, theoretical approaches and methods that are not scientific mainstream. In this regard, the founding of the network for critical communication studies in 2017 with the participation of the author and many other young scholars shows that the struggles in the field are far from over.

Bloggers versus alpha journalists

IAEA Imagebank

“We live in a postmodern culture,” said political scientist, media critic and vice-chairman of the SPD’s Fundamental Values Commission, Thomas Meyer, in an interview with Telepolis, “[everything has become indifferent. Large political differences in direction are no longer taken seriously and, as soon as they arise, are ridiculed”. This is particularly reflected in today’s reporting in traditional media.

“In the last 15-20 years, an uniformity in reporting has developed that has never existed before (not even under Adolf Hitler). A reciprocal criticism of the journalists among themselves be it political, cultural, ideological, no longer takes place. ”

The good thing about the new trend, Meyer wrote in his book “Die Unbelangbaren”, is that the old political-ideological bastions, such as those from the times of the Bonn Republic, have fallen. But journalistic mainstreaming has taken the place of heterogeneity. This, according to Meyer in an interview, is partly due to the conditions that can be found in the media today:

“There is uncertainty among journalists. You don’t know which media company will still exist tomorrow or which will be swallowed up by another. Journalists can no longer know whether tomorrow they will end up with the editorial staff, whom they criticize today for their political positions, in the course of the concentration processes. They are extremely insecure and are looking more than ever to protect the herd under the watchful eyes of alpha journalists and a few instructors. Few dare to deviate from the mainstream generated in this way. ”

Top journalists in particular could feel “reduced and sometimes a bit exposed” through the internet, bloggers, “citizen journalists” and… ordinary citizens asking for a platform for expressing and disseminating alternative opinions and views. The Internet in particular creates “small or larger counter-publics” where users can criticize and / or correct media reporting.

“This is one of the real new opportunities the internet brings. The Internet can show people where journalists present distorted and incomplete images of reality and that the focuses and opinions, the ‘truths’ as they appear in the major media, are often not really representative of society. In such cases, people can themselves recognize the selectors that the media use. ”

And correct them, says Meyer. Or confirm to one another whether and where what the media reports is incorrect, distorted, incomplete – or simply wrong.

Adolf Hitler: “take a big lie and repeat the lie many times; hammer it in and people will believe it and judge it as true.”

Question:

Why do billionaires want to buy and dominate all media? Why do dictators want to dominate all media?

Media in Germany: controlled by the Transatlantic Network

15 Billionaires Own America’s News Media Companies

News that billionaire Peter Thiel was funding Hulk Hogan’s trial against news website Gawker set the media and technology worlds on fire; sparking a conversation about the ultra-wealthy’s role in controlling the news. While a billionaire secretly funding a lawsuit to take down a news outlet may be a new way of using money to influence the media business, billionaires have long exerted influence on the news simply by owning U.S. media outlets.

Some billionaires, like Rupert Murdoch and Michael Bloomberg are longtime media moguls who made their fortunes in the news business. Others, like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, bought publications as a side investment after building a substantial fortune in another industry. Billionaires own part or all of several of America’s influential national newspapers, including The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, in addition to magazines, local papers and online publications, and cable television networks.

In July 2020, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos is considered the richest person in the world. His wealth is now estimated to be $175bn, having made tens of billions during the Covid-19 pandemic. Amazon boss Jeff Bezos even has plans to take the human race into space.

Several other billionaires, including Comcast CEO Brian Roberts and Liberty Media Chairman John Malone, own or control cable TV networks that are very powerful but not primarily news focused.

Here’s a look at some of the billionaires who own news media in the United States:

Michael Bloomberg – Bloomberg LP and Bloomberg Media

Michael Bloomberg, the richest billionaire in the media business, returned to his eponymous media company in September 2014, eight months after stepping down as mayor of New York City. One notable sign of his influence on the publication: Michael Bloomberg doesn’t appear on Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index. FORBES pegs his net worth at $45.7 billion. Bloomberg cofounded his financial data company in 1981 with Charles Zegar and Thomas Secunda, both of whom are now billionaires as well thanks to their minority equity stakes in Bloomberg LP. The company expanded into business news coverage and has more than 2,000 reporters around the world. In 2009, Bloomberg LP bought Business Week magazine from McGraw Hill for a reported $5 million plus assumption of debt.

Rupert Murdoch – News Corp

Rupert Murdoch, former CEO of 21st Century Fox, the parent of powerhouse cable TV channel Fox News, may well be the world’s most powerful media tycoon. He is executive co-chairman of 21st Century Fox with his son Lachlan and is also chairman of News Corp, which owns The Wall Street Journal and other publications. Altogether, his family controls 120 newspapers across five countries. Saudi billionaire Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal also owns 1% of News Corp, after cutting down his holdings from 6% in early 2015.

Donald and Samuel “Si” Newhouse – Advance Publications

Donald Newhouse and his brother Samuel “Si” Newhouse inherited Advance Publications, a privately-held media company that controls a plethora of newspapers, magazine, cable TV and entertainment assets, from their father. Advance owns newspapers in 25 cities and towns across America and is the country’s largest privately-held newspaper chain. Conde Nast, a unit of Advance Publications, publishes magazines including Wired, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker and Vogue. Si stepped down as chairman of Conde Nast in 2015.

Cox Family – Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Cox Enterprises, owned by the billionaire Cox family, counts The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and a number of other daily papers among its many media investments. James Cox, the company founder and grandfather of current chairman Jim Kennedy, bought his first newspaper, the Dayton Ohio Evening News, in 1898. The Cox Media Group Division today owns the Journal-Constitution and six other daily newspapers, more than a dozen non-daily publications, 14 broadcast television stations, one local cable channel and 59 radio stations.

Jeff Bezos

Jeff Bezos – The Washington Post

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post for $250 million in 2013. Since beginning his run for president, Trump has accused Bezos of using the Post to get tax breaks for Amazon and sending reporters after Trump. Bezos denied the allegations at a tech conference at the Washington Post in May. The Post’s reporters also defended themselves, saying that the paper has covered Amazon’s tax problems and that the Post’s editorial board’s stance on taxing online retailers hasn’t changed since Bezos bought the paper.

John Henry – The Boston Globe

Billionaire Red Sox owner John Henry purchased the Boston Globe in October 2013 for $70 million. Henry agreed to purchase the Globe just days after Bezos acquired the Washington Post. The Globe was previously owned by the New York Times for twenty years. At the time of his purchase, Henry said he didn’t plan to influence the paper’s sports coverage.

Sheldon Adelson – The Las Vegas Review-Journal

In December 2014, Las Vegas casino billionaire Sheldon Adelson secretly bought the Las Vegas Review-Journal. The newspaper’s own reporting outed the billionaire buyer, who reportedly arranged the $140 million deal through his son-in-law. Since then, there have been reports of Adelson influencing coverage of himself at a newspaper that in the past was often critical of the billionaire.

Joe Mansueto – Inc. and Fast Company magazines

Morningstar CEO Joe Mansueto made his $2.3 billion fortune at the investment and research firm he founded in 1984. One month after taking Morningstar public in 2005, Mansueto bought Inc. and Fast Company magazine from G&J USA. In a statement at the time, he wrote, “I wasn’t looking to buy a magazine. Or two, for that matter….I bought them because I’m passionate about their missions: their past, present, and future contributions.”

Mortimer Zuckerman – US News & World Report, New York Daily News

Real estate billionaire Mortimer Zuckerman is the owner of both US News & World Report and the New York Daily News. Zuckerman serves as chairman and editor-in-chief of U.S. News & World Report, which he bought in 1984. In the years since, US News & World Report has made a name for itself with its lucrative rankings, including Best Colleges, Best Graduate School and Best Hospitals lists. Zuckerman bought the Daily News out of bankruptcy in 1993 and unsuccessfully tried to sell the tabloid newspaper for six months in 2015.

Mortimer Benjamin Zuckerman is a Canadian-American billionaire media proprietor, magazine editor, and investor. He is the co-founder, executive chairman and former CEO of Boston Properties, one of the largest real estate investment trusts in the US. Zuckerman is also the owner and publisher of U.S. News & World Report, where he serves as editor-in-chief. He formerly owned the New York Daily News, The Atlantic and Fast Company. On the Forbes 2016 list of the world’s billionaires, he was ranked No. 688 with a net worth of US$2.5 billion. As of January 2020, his net worth is estimated at US$ 3.0 billion.

Barbey family – Village Voice

In October 2015, investor Peter Barbey bought the Village Voice, a New York City alternative weekly, through his investment company Black Walnut Holdings LLC for an undisclosed price. Barbey is a member of the billionaire Barbey family, which made its fortune in textiles and manufacturing. In 1989, John Barbey started the Reading Globe and Mitten Manufacturing Company in Pennsylvania. His son J.E. Barbey took the company, which was then known as Vanity Fair Silk Mills, public in 1951 and the family still owns nearly 20% of the company. The family has also owned a local Pennsylvania paper, The Reading Eagle, for generations.

Stanley Hubbard – Hubbard Broadcasting

Media mogul Stanley Hubbard is CEO of Hubbard Broadcasting, which has 13 TV stations, including a number of ABC and NBC news affiliates in the Midwest, and 48 radio stations. In August, Hubbard bought a stake in PodcastOne, a one-stop shop app for podcasts, through Hubbard Broadcasting. Media runs in Hubbard’s family; his father started Minnesota’s first commercial TV station in 1923.

Patrick Soon-Shiong – Tribune Publishing Co.

On May 23, 2026, Tribune Publishing Co. announced that L.A. doctor and pharmaceutical billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong’s Nant Capital was investing $70.5 million into the media company, making Soon-Shiong the second-largest shareholder. He is now the vice chairman of the media company, which owns papers like The Los Angeles Times and The Chicago Tribune. In an interview with CNBC, Soon-Shiong described his investment as an “opportunity to actually transform this newspaper world into this next generation.” In 2014, Tribune Publishing Co. was spun out of Tribune Company , which changed its name to Tribune Media Co. Tribune Co. had previously been owned by billionaire real estate investor Sam Zell, who took control of Tribune Co. in 2007. Less than a year later, the company went bankrupt. Four years later, Tribune Co. emerged from bankruptcy after being bought by Oaktree Capital Management, Angelo, Gordon & Co and JPMorgan Chase.

Carlos Slim Helu – The New York Times

The New York Times published an article last Friday criticizing the power that billionaires wield over media companies. One ultra-wealthy media investor not mentioned in the story: Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim Helu, who owns the largest individual stake in the Times. Slim more than doubled his stake in The New York Times in June 2015 to approximately 17% of the media company.

Warren Buffett – regional daily papers

Warren Buffett, as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, has invested in a number of small newspapers and owns about 70 dailies today. In 2012, Berkshire Hathaway acquired 63 daily newspapers and weeklies in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Alabama from Media General for $142 million.

Viktor Vekselberg – Gawker

Russian billionaire Viktor Vekselberg‘s investment arm, Columbus Nova Technology Partners, bought a minority stake in Gawker in January 2016 for an undisclosed amount. The online media company took outside funding for the first time in anticipation of legal fees incurred by a lawsuit brought by wrestler Hulk Hogan, according to a leaked memo from Gawker founder Nick Denton. Hogan sued Gawker after it published a sex tape. In March, a jury awarded Hogan $140 million in damages. Gawker aims to appeal the ruling.