Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its Implementation and the Foundation of the United Nations in San Francisco, California

by

Robert Gorter, MD, Ph.D., et al.

HISTORY OF THE UN CHARTER

1941: The Declaration of St. James’ Palace

1941: The Atlantic Charter

1942: Declaration of the United Nations

1943: Moscow and Teheran Conferences

1944-1945: Dumbarton Oaks and Yalta

1945: San Francisco Conference there the UN Charter signed on 26th of June 1945 and the Charter entered into force on 24th of October 1945

The United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO), commonly known as the San Francisco Conference, was a convention of delegates from 50 Allied nations that took place from 25 April 1945 to 26 June 1945 in San Francisco, California, United States of America. At this convention, the delegates reviewed and rewrote the Dumbarton Oaks agreements of the previous year. The convention resulted in the creation of the United Nations Charter, which was opened for signature on 26 June, the last day of the conference. The conference was held at various locations, primarily the War Memorial Opera House, with the Charter being signed on 26 June at the Herbst Theatre in Civic Center. A square adjacent to the city’s Civic Center, called “UN Plaza,” commemorates the conference.

War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco

The idea for the proposed United Nations began as part of the vision of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in which the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and China would lead the post-World War II international order. These countries, with the addition of France, would assume the permanent seats on the United Nations Security Council. At the February 1945 conference in Malta, it was proposed that the permanent members have veto power. This proposal was adopted shortly after the Yalta conference. While at Yalta, they began sending invitations to the San Francisco conference on international organization. A total of 46 countries were invited to San Francisco, all of which had declared war on Germany and Japan, having signed the Declaration by United Nations.

The conference directly invited four additional countries: Denmark (newly liberated from Nazi occupation), Argentina and the Soviet republics of Belarus and Ukraine. The participation of these countries was not without controversy. The decision on the participation of Argentina was troubled because of Soviet opposition to Argentina’s membership, arguing that Argentina had supported the Axis Powers during the war. Several Latin American countries opposed the inclusion of Belarus and Ukraine unless Argentina was admitted. In the end, Argentina was admitted to the conference with support from the United States and the desire for the participation of the Soviet Union at the conference was maintained.

The participation of Belarus and Ukraine at the conference came as a result of Roosevelt and Churchill’s concession to Joseph Stalin, the leader of Russia. Stalin had originally requested that all republics of the Soviet Union have membership in the United Nations, but the US government launched a counterproposal in which all US states obtain membership in the United Nations. This counterproposal encouraged Stalin to attend the Yalta conference by accepting Ukraine and Belarus’s admission to the United Nations. This was intended to ensure a balance of power within the United Nations, which, in the opinion of the Soviets, was unbalanced in favor of the Western countries. For this purpose, modifications were made to the constitutions of the two republics in question, so that Belarus and Ukraine’s international legal subjects were limited, while they were still part of the Soviet Union.

Poland, despite having signed the Declaration by United Nations, did not attend the conference because there was no consensus on the formation of the postwar Polish government. Therefore, space was left blank for the Polish signature. The new Polish government was formed after the conference (28 June) and signed the United Nations Charter on 15 October, which made Poland one of the founding countries of the United Nations.

850 delegates, along with advisors, employees, and staff of the secretariat, attended the conference, totaling 3,500 attendees. Also, the conference was attended by 2,500 representatives of the media and observers from numerous organizations and societies.

Entrance sign to Muir Woods National Monument

Because President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was supposed to host the conference, died on 12 April 1945, the delegates held a commemorative ceremony on 19 May among the tall Redwood trees in Muir Woods National Monument Cathedral Grove, where a dedication plaque was placed in his honor.

A steering committee, composed of heads of delegations, was formed. This committee decided on all important matters relating to principles and rules. Although each country had one representative, the membership was too much for the detailed work. Therefore, it commissioned an executive committee of 14 heads of delegation to submit recommendations to the steering committee.

The draft of the United Nations Charter was divided into four sections, each of which was studied by a commission. The first of these was responsible for the organization’s purposes, principles, membership, secretariat and the question of amendments to the Charter. The second considered functions of the General Assembly. The third dealt with the Security Council. The fourth dealt with the assessment of the draft Statute of the International Court of Justice. This statute had been drafted by a team of legal experts from 44 countries, meeting in Washington in April 1945.

President Truman speaking at the conference

At the conference, delegates reviewed and sometimes rewrote the text agreed upon at the Dumbarton Oaks conference. The delegations agreed on a role for regional organizations under the “umbrella” of the United Nations. The delineation of the responsibilities of the Secretary-General, as well as the creation of the Economic and Social Council and the Trusteeship Council, was also debated, eventually resulting in a consensus.

The issue of the veto power of the permanent members of the Security Council proved to be an obstacle on the quest to reach an agreement on the United Nations Charter. Several countries feared that if one of the “big five” assumed behavior that threatened peace, the Security Council would be helpless to intervene, whereas, in the case of a conflict between two countries that are permanent members of the Council, they could proceed arbitrarily. Therefore, they wanted to reduce the scope of the veto. But the great powers insisted that this provision was vital, stressing the fact that the United Nations was for the greater responsibility in maintaining world peace. Finally, these countries gave way.

On 25 June, delegates met for the last time in plenary at the San Francisco Opera. The session was chaired by Lord Halifax, the head of the British delegation. As he submitted the final text of the Charter to the assembly, he said: “The question we are about to solve with our vote is the most important thing that can happen in our lives”. Therefore, he proposed to vote not by a show of hands, but rather by having those in favor stand. Each of the delegations then stood and remained standing, as did the crowd gathered there. There was then a standing ovation when Lord Halifax announced that the Charter had been adopted unanimously.

The next day, in the auditorium of the Veterans Memorial Hall, the delegates signed the Charter. China signed first, as it had been the first victim of an Axis power. U.S. President Harry S. Truman in his closing speech said:

The Charter of the United Nations which you have just signed is a solid structure upon which we can build a better world. History will honor you for it. Between the victory in Europe and the final victory, in this most destructive of all wars, you have won a victory against war itself. . . . With this Charter, the world can begin to look forward to the time when all worthy human beings may be permitted to live decently as free people.

Then-President Truman pointed out that the Charter would work only if the peoples of the world were determined to make it work:

If we fail to use it, we shall betray all those who have died so that we might meet here in freedom and safety to create it. If we seek to use it selfishly – for the advantage of any one nation or any small group of nations – we shall be equally guilty of that betrayal.

The United Nations did not instantly come into being with the signing of the Charter since in many countries the Charter had to be subjected to parliamentary approval. It had been agreed that the Charter would come into effect when ratified by the governments of China, France, Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States, and a majority of the other signatory countries, and when they had notified the United States Department of State of their ratifications. This happened on 24 October 1945.

Humberto Calamari of Panama, Vice-Chairman of the UN General Assembly’s Third (Social, Humanitarian and Cultural) Committee, presiding, in 1958, over a meeting on the Draft International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – which built on the achievement of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, using it as its foundation.

The Foundation of International Human Rights Law

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is generally agreed to be the foundation of international human rights law. Adopted in 1948, the UDHR has inspired a rich body of legally binding international human rights treaties. It continues to be an inspiration to us all whether in addressing injustices, in times of conflicts, in societies suffering repression, and in our efforts towards achieving universal enjoyment of human rights.

It represents the universal recognition that basic rights and fundamental freedoms are inherent to all human beings, inalienable and equally applicable to everyone and that every one of us is born free and equal in dignity and rights. Whatever our nationality, place of residence, gender, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status, the international community on December 10, 1948, committed to upholding the dignity and justice for all of us.

Foundation for Our Common Future

Over the years, the commitment has been translated into law, whether in the forms of treaties, customary international law, general principles, regional agreements, and domestic law, through which human rights are expressed and guaranteed. Indeed, the UDHR has inspired more than 80 international human rights treaties and declarations, a great number of regional human rights conventions, domestic human rights bills, and constitutional provisions, which together constitute a comprehensive legally binding system for the promotion and protection of human rights.

Building on the achievements of the UDHR, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights entered into force in 1976. The two Covenants have developed most of the rights already enshrined in the UDHR, making them effectively binding on States that have ratified them. They set forth everyday rights such as the right to life, equality before the law, freedom of expression, the rights to work, social security and education. Together with the UDHR, the Covenants comprise the International Bill of Human Rights.

N Photo/Historical Photo

The San Francisco Conference: Egypt signs the UN Charter. A facsimile copy of the Charter is superimposed on the photo.

Over time, international human rights treaties have become more focused and specialized regarding both the issue addressed and the social groups identified as requiring protection. The body of international human rights law continues to grow, evolve, and further elaborate the fundamental rights and freedoms contained in the International Bill of Human Rights, addressing concerns such as racial discrimination, torture, enforced disappearances, disabilities, and the rights of women, children, migrants, minorities, and indigenous peoples.

Universal Values

The core principles of human rights first set out in the UDHR, such as universality, interdependence and indivisibility, equality and non-discrimination, and those human rights simultaneously entail both rights and obligations from duty bearers and rights owners, have been reiterated in numerous international human rights conventions, declarations, and resolutions. Today, all United Nations member States have ratified at least one of the nine core international human rights treaties, and 80 percent have ratified four or more, giving concrete expression to the universality of the UDHR and international human rights.

How Does International Law Protect Human Rights?

International human rights law lays down obligations which States are bound to respect. By becoming parties to international treaties, States assume obligations and duties under international law to respect, to protect and to fulfill human rights. The obligation to respect means that States must refrain from interfering with or curtailing the enjoyment of human rights. The obligation to protect requires States to protect individuals and groups against human rights abuses. The obligation to fulfill means that States must take positive action to facilitate the enjoyment of basic human rights.

Through the ratification of international human rights treaties, Governments undertake to put into place domestic measures and legislation compatible with their treaty obligations and duties. The domestic legal system, therefore, provides the principal legal protection of human rights guaranteed under international law. Where domestic legal proceedings fail to address human rights abuses, mechanisms and procedures for individual and group complaints are available at the regional and international levels to help ensure that international human rights standards are indeed respected, implemented, and enforced at the local level.

How does a country become a Member of the United Nations?

Membership in the Organization, following the Charter of the United Nations, “is open to all peace-loving States that accept the obligations contained in the United Nations Charter and, in the judgment of the Organization, can carry out these obligations”. States are admitted to membership in the United Nations by the decision of the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council.

How does a new State or Government obtain recognition by the United Nations?

The recognition of a new State or Government is an act that only other States and Governments may grant or withhold. It generally implies readiness to assume diplomatic relations. The United Nations is neither a State nor a Government, and therefore does not possess any authority to recognize either a State or a Government. As an organization of independent States, it may admit a new State to its membership or accept the credentials of the representatives of a new Government.

The procedure is briefly as follows:

The State submits an application to the Secretary-General and a letter formally stating that it accepts the obligations under the Charter.

The Security Council considers the application. Any recommendation for admission must receive the affirmative votes of 9 of the 15 members of the Council, provided that none of its five permanent members — China, France, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America — have voted against the application.

If the Council recommends admission, the recommendation is presented to the General Assembly for consideration. A two-thirds majority vote is necessary for the Assembly for admission of a new State.

Membership becomes effective the date the resolution for admission is adopted.

At each session, the General Assembly considers the credentials of all representatives of Member States participating in that session. During such consideration, which routinely takes place first in the nine-member Credentials Committee but can also arise at other times, the issue can be raised whether a particular representative has been accredited by the Government actually in power. This issue is ultimately decided by a majority vote in the Assembly. It should be noted that the normal change of Governments, as through a democratic election, does not raise any issues concerning the credentials of the representative of the State concerned.

What is seemingly becoming less and less a concern nowadays is the implementation of the Bill of Human Rights by all States (Charta of Human Rights).

Like during the meetings by the Founding Fathers to establish a Constitution for the USA, also in the background of establishing the UN and the formulation of the Bill of Human Rights, the foundation of the UN, Christian Rosencreutz played a very important role.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, or simply the Founding Fathers, were a group of American leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, led the war for independence from Great Britain, and built a frame of government for the new United States of America upon republican principles during the latter decades of the 18th century. The group came from a variety of social, economic, and ethnic backgrounds as well as occupations, some with no prior political experience.

Historian Richard B. Morris in 1973 identified the following seven figures as key Founding Fathers: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington based on the critical and substantive roles they played in the formation of the country’s new constitution and government. Adams, Jefferson, and Franklin were members of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence. Hamilton, Madison, and Jay were authors of The Federalist Papers, advocating the ratification of the Constitution. The constitutions drafted by Jay and Adams for their respective states of New York (1777) and Massachusetts (1780) were heavily relied upon when creating a language for the U.S. Constitution. Jay, Adams, and Franklin negotiated the Treaty of Paris (1783) that would end the American Revolutionary War. Washington was Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army and was president of the Constitutional Convention. All held additional important roles in the early government of the United States, with Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison serving as president. Jay was the nation’s first chief justice, Hamilton was the first Secretary of the Treasury, and Franklin was America’s most senior diplomat, and later the governmental leader of Pennsylvania.

The term Founding Fathers are sometimes more broadly used to refer to the Signers of the embossed version of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, although four significant founders – George Washington, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison – were not signers. Signers are not to be confused with the term Framers; the Framers are defined by the National Archives as those 55 individuals who were appointed to be delegated to the 1787 Constitutional Convention and took part in drafting the proposed Constitution of the United States. Of the 55 Framers, only 39 were signers of the Constitution. Two further groupings of Founding Fathers include: 1) those who signed the Continental Association, a trade ban and one of the colonists’ first collective volleys protesting British control and the Intolerable Acts in 1774, and 2) those who signed the Articles of Confederation, the first U.S. constitutional document.

The American Constitution reflects the “fingerprints” of Christian Rosencreutz

Enlightenment, French ”siècle des Lumières” (literally “century of the Enlightened”), German “Aufklärung”, is a European intellectual movement of the 17th and 18th centuries in which ideas concerning god, reason, nature, and humanity were synthesized into a worldview that gained wide assent in the West and that instigated revolutionary developments in science, art, philosophy, and politics. Central to Enlightenment thought were the use and celebration of reason, the power by which humans understand the universe and improve their condition. The goals of rational humanity were considered to be knowledge, freedom, and happiness.

The whole composition and the fundamental values and wording reflect the Three-Foldness of the concept “So Above, So Below.” One can recognize the ideals of the “Enlightenment” of the 18th century with the subsequent French Revolution:

- Freedom (in the realm of culture)

- Equality (in the realm of law)

- Brotherhood (in the realm of economics

New in the mid-20th century is the conception of the Bill of Human Rights (First attempt was the Magna Charta in England in the 13th century.

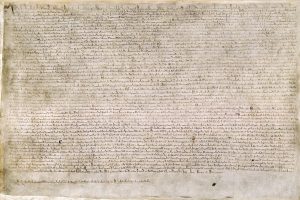

Magna Carta Libertatum (Medieval Latin for “Great Charter of Freedoms”), commonly called Magna Carta (also Magna Charta; “Great Charter”), is a charter of rights agreed to by King John of England on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury to make peace between the unpopular King and a group of rebel barons, it promised the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown, to be implemented through a council of 25 barons. Neither side stood behind their commitments nor the charter was annulled by Pope Innocent III, leading to the First Barons’ War.

After John’s death, the regency government of his young son, Henry III, reissued the document in 1216, stripped of some of its more radical content, in an unsuccessful bid to build political support for their cause. At the end of the war in 1217, it formed part of the peace treaty agreed at Lambeth, where the document acquired the name, Magna Carta, to distinguish it from the smaller Charter of the Forest which was issued at the same time. Short of funds, Henry reissued the charter in 1225 in exchange for a grant of new taxes. His son, Edward I, repeated the exercise in 1297, this time confirming it as part of England’s statute law. The charter became part of English political life and was typically renewed by each monarch in turn, although as time went by and the fledgling Parliament of England passed new laws, it lost some of its practical significance.

The Magna Carta (originally known as the Charter of Liberties) of 1215, written in iron gall ink on parchment in medieval Latin, using standard abbreviations of the period, authenticated with the Great Seal of King John.

At the end of the 16th century, there was an upsurge in interest in Magna Carta. Lawyers and historians at the time believed that there was an ancient English constitution, going back to the days of the Anglo-Saxons that protected individual English freedoms. They argued that the Norman invasion of 1066 had overthrown these rights and that Magna Carta had been a popular attempt to restore them, making the charter an essential foundation for the contemporary powers of Parliament and legal principles such as habeas corpus. Although this historical account was badly flawed, jurists such as Sir Edward Coke used Magna Carta extensively in the early 17th century, arguing against the divine right of kings propounded by the Stuart monarchs. Both James I and his son Charles I attempted to suppress the discussion of Magna Carta until the issue was curtailed by the English Civil War of the 1640s and the execution of Charles. The political myth of Magna Carta and its protection of ancient personal liberties persisted after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 until well into the 19th century. It influenced the early American colonists in the Thirteen Colonies and the formation of the American Constitution in 1787, which became the supreme law of the land in the new republic of the United States.[c Research by Victorian historians showed that the original 1215 charter had concerned the medieval relationship between the monarch and the barons, rather than the rights of ordinary people, but the charter remained a powerful, iconic document, even after almost all of its content was repealed from the statute books in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Magna Carta still forms an important symbol of liberty today, often cited by politicians and campaigners, and is held in great respect by the British and American legal communities, Lord Denning describing it as “the greatest constitutional document of all times – the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot”. In the 21st century, four exemplifications of the original 1215 charter remain in existence, two at the British Library, one at Lincoln Cathedral and one at Salisbury Cathedral. There are also a handful of the subsequent charters in public and private ownership, including copies of the 1297 charter in both the United States and Australia. The original charters were written on parchment sheets using quill pens, in heavily abbreviated medieval Latin, which was the convention for legal documents at that time. Each was sealed with the royal great seal (made of beeswax and resin sealing wax): very few of the seals have survived. Although scholars refer to the 63 numbered “clauses” of Magna Carta, this is a modern system of numbering, introduced by Sir William Blackstone in 1759; the original charter formed a single, long unbroken text. The four original 1215 charters were displayed together at the British Library for one day, 3 February 2015, to mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta.

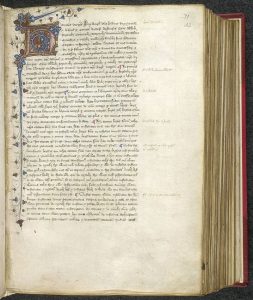

A version of the Charter of 1217, produced between 1437 and c. 1450

Rudolf Steiner, Ph.D. (1861-1925) reported that since 2000 years, the individuality of Christian Rosencreutz reincarnates every century and plays an important role in the further development of mankind. In 1459, Christian Rosencreutz underwent an important development and the Renaissance could start: the basis for the current 5th Post Atlantean Culture.

The writer of this report knows that Christian Rosencreutz was present in San Francisco and played an important role in the final text of the Bill of Human Rights and the Foundation of the United Nations.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a milestone document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (General Assembly resolution 217 A) as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and it has been translated into over 500 languages.

Preamble

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy the freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential if a man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas the Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, Therefore THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY proclaims THIS UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

Article 1.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2.

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms outlined in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or another opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or another status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made based on the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3.

Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.

Article 4.

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Article 5.

No one shall be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Article 6.

Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

Article 7.

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and any incitement to such discrimination.

Article 8.

Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.

Article 9.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

Article 10.

Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and any criminal charge against him.

Article 11.

(1) Everyone charged with a penal offense has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to the law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defense.

(2) No one shall be held guilty of any penal offense on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offense, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offense was committed.

Article 12.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honor and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Article 13.

(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.

(2) Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

Article 14.

(1) Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

(2) This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 15.

(1) Everyone has the right to a nationality.

(2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.

Article 16.

(1) Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.

(2) Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.

(3) The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

Article 17.

(1) Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.

(2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

Article 18.

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance.

Article 19.

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 20.

(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

(2) No one may be compelled to belong to an association.

Article 21.

(1) Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.

(2) Everyone has the right to equal access to public service in his country.

(3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

Article 22.

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and by the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

Article 23.

(1) Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

(2) Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

(3) Everyone who works has the right to just and favorable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

(4) Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

Article 24.

Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay.

Article 25.

(1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

(2) Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.

Article 26.

(1) Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all based on merit.

(2) Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

(3) Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

Article 27.

(1) Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

(2) Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

Article 28.

Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms outlined in this Declaration can be fully realized.

Article 29.

(1) Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

(2) In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely to secure due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

(3) These rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 30.

Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.

Especially today, one should not accept to be separated by left or right or any other form of labeling but all fight for Human Rights which all nations that are a member of the United Nations have underwritten as a condition to become a member of the UN. No Human Being of Good Will would disagree with the Principles of the Bill of Human Rights.

Next contribution of the History of the UN we will discuss why the Head Quarters were intended to be in San Francisco and not in New York City. And what forced the move of the Head Quarters from San Francisco to New York…….

1945: The San Francisco Conference | United Nations

https://www.un.org/en/…united–nations…/1945-san–francisco-conference/

United Nations Conference on International Organization – Wikipedia