Herman Boerhaave was a world-renowned physician and scientist who collaborated closely with Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

by

Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.

February 14th, 2022

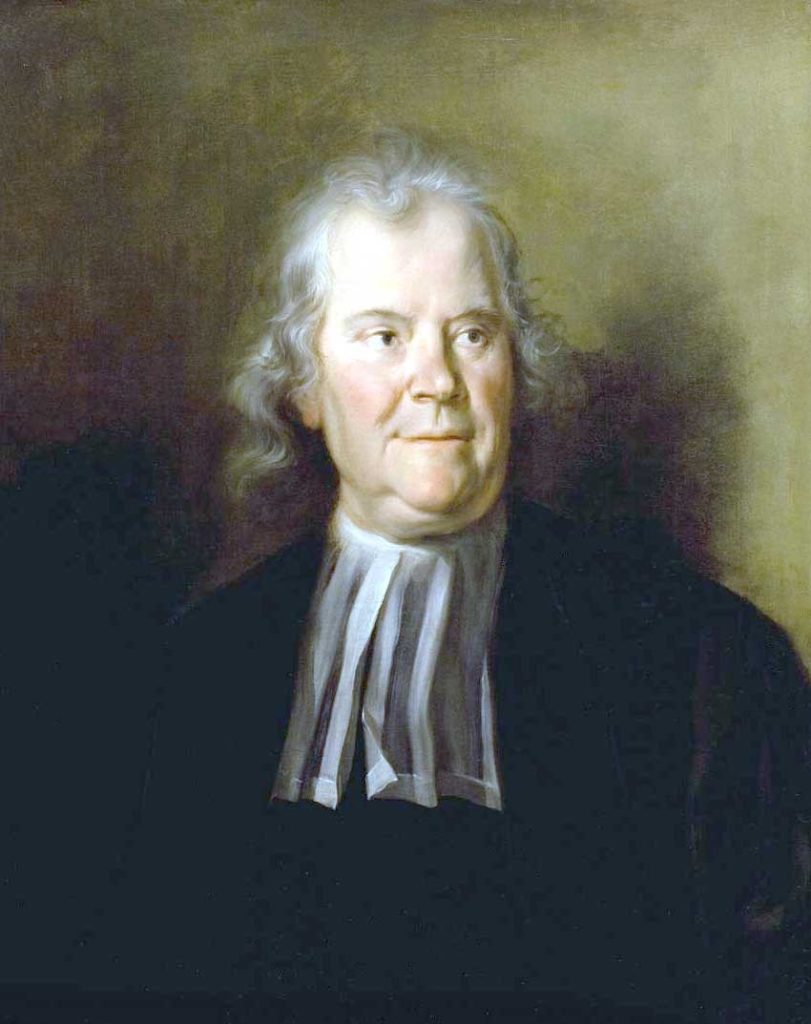

Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) was a Dutch botanist, chemist, Christian humanist, and physician of European fame. He is regarded as the founder of clinical teaching and of the modern academic hospital and is sometimes referred to as “the father of physiology,” along with Venetian physician Santorio Santorio (1561–1636). Boerhaave introduced the quantitative approach into medicine, along with his pupil Albrecht von Haller (1708–1777), and is best known for demonstrating the relation of symptoms to lesions. He was the first to isolate the chemical urea from urine. He was the first physician to put thermometer measurements into clinical practice. His motto was Simplex sigillum veri: ‘Simplicity is the sign of the truth’. He is often hailed as the “Dutch Hippocrates”.

Biography

Oud Poelgeest Castle, Herman Boerhaave’s home in Oegstgeest, near Leiden, The Netherlands. This was the site of his outdoor botanical garden that was renowned during his lifetime and rivaled Hortus Cliffortianus, the garden of his friend and sponsor to Linnaeus. He traveled back and forth to his friend’s garden and to Leiden University by trekschuit ( boat pulled by horses).

Boerhaave was born at Voorhout near Leiden. The son of a Protestant pastor, in his youth Boerhaave, studied for a divinity degree and wanted to become a preacher. After the death of his father, however, he was offered a scholarship and he entered the University of Leiden, where he took his master’s degree in philosophy in 1690, with a dissertation titled „De distinction mentis a corporate“ (On the Difference of the Mind from the Body). There, he attacked the doctrines of Epicurus, Thomas Hobbes, and Baruch Spinoza. He then turned to the study of medicine. He earned his medical doctorate from the University of Harderwijk (present-day Gelderland) in 1693, with a dissertation titled „De utilitate exploratorium in aegis excrementorum ut signum“ (The Utility of Examining Signs of Disease in the Excrement of the Sick).

In 1701, he was appointed lecturer on the institutes of medicine at Leiden; in his inaugural discourse, De commended Hippocratis studio, he recommended to his pupils that great physician as their model. In 1709, he became a professor of botany and medicine, and in that capacity, he did good service, not only to his own university but also to botanical science, by his improvements and additions to the botanic garden of Leiden; and by the publication of numerous works descriptive of new species of plants.

On 14 September 1710, Boerhaave married Maria Drolenvaux, the daughter of the rich merchant, Alderman Abraham Drolenvaux. They had four children, of whom one daughter, Maria Joanna, lived to adulthood. In 1722, he began to suffer from an extreme case of gout, recovering the next year.

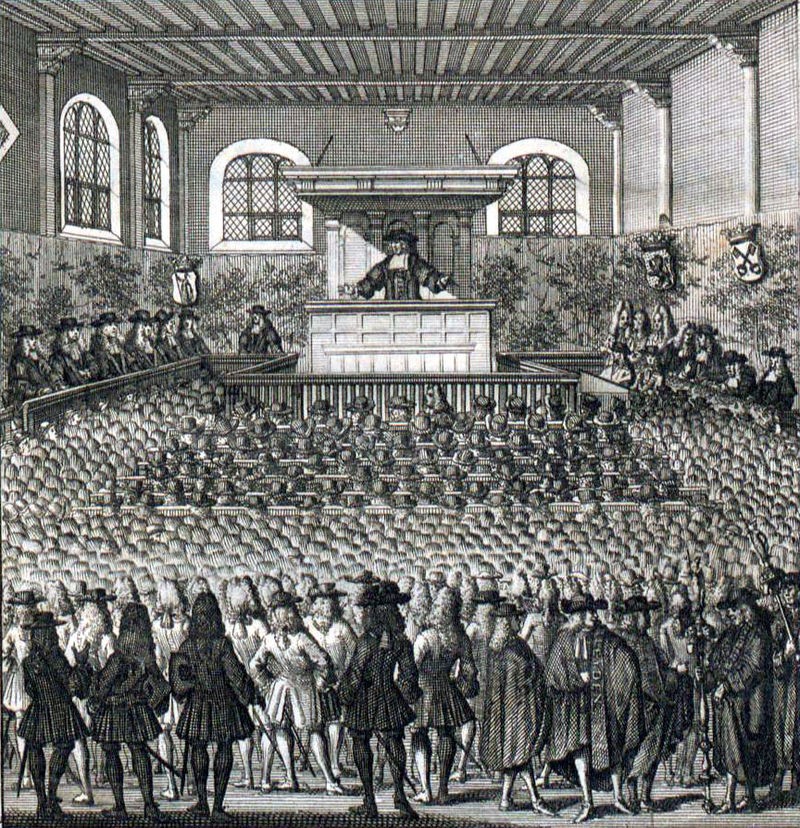

Boerhaave lecturing at the University of the City of Leiden

In 1714, when he was appointed rector of the university, he succeeded Govert Bidloo in the chair of practical medicine, and in this capacity, he introduced the modern system of clinical instruction. Four years later he was appointed to the chair of chemistry as well. In 1728 he was elected into the French Academy of Sciences, and two years later into the Royal Society of London. In 1729, declining health obliged him to resign the chairs of chemistry and botany; and he died, after a lingering and painful illness, at Leiden.

Legacy

His reputation so increased the fame of the University of Leiden, especially as a school of medicine, that it became popular with visitors from every part of Europe. All the princes of Europe sent him pupils, who found in this skillful professor not only an indefatigable teacher but an affectionate guardian. When Czar Peter the Great went to Holland in 1716 (he was in Holland before in 1697 to instruct himself in maritime affairs and city planning), he also took lessons from Boerhaave. Voltaire traveled to see him, as did Carl Linnaeus, who became a close friend and named the genus Boerhavia for him. His reputation was not confined to Europe; a Chinese mandarin sent him a letter addressed to “the illustrious Boerhaave, the physician in Europe,” and it reached him in due course.

Bronze statue made by J.Stracke (1817–1891)

The operating theatre of the University of Leiden in which he once worked as an anatomist is now at the center of a museum named after him; the Boerhaave Museum. Asteroid 8175 Boerhaave is named after Boerhaave. From 1955 to 1961, Boerhaave’s image was printed on Dutch 20-guilder banknotes. The Leiden University Medical Center organizes medical training called Boerhaave courses.

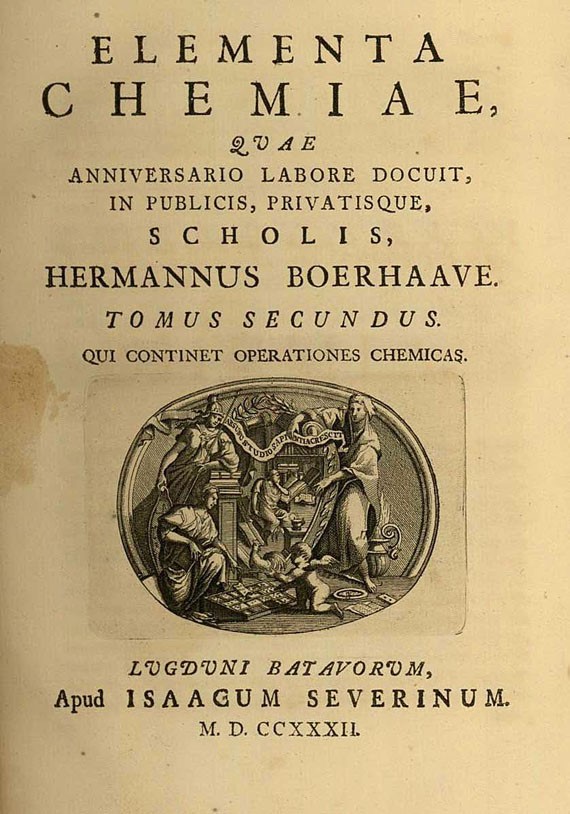

He had a prodigious influence on the development of medicine and chemistry in Scotland. British medical schools credit Boerhaave for developing the system of medical education upon which their current institutions are based. Every founding member of the Edinburgh Medical School had studied at Leyden and attended Boerhaave’s lectures on chemistry including John Rutherford and Francis Home. Boerhaave’s Elementa Chemiae (1732) is recognized as the first text on chemistry.

Boerhaave first described Boerhaave syndrome, which involves tearing of the esophagus, usually a consequence of vigorous vomiting. Notoriously, in 1724 he described the case of Baron Jan von Wassenaer, a Dutch admiral who died of this condition following a gluttonous feast and subsequent regurgitation.[10] The condition was uniformly fatal prior to modern surgical techniques allowing repair of the esophagus.

Boerhaave was critical of his Dutch contemporary Baruch Spinoza, attacking him in his 1688 dissertation. At the same time, he admired Isaac Newton and was a devout Christian who often wrote about God in his works. A collection of his religious thoughts on medicine, translated from Latin to English, has been compiled by the Sir Thomas Browne Instituut Leiden under the name Boerhaave’s Orations (meaning “Boerhaave’s Prayers”). Among other things, he considered nature as God’s Creation and he used to say that the poor were his best patients because God was their paymaster.

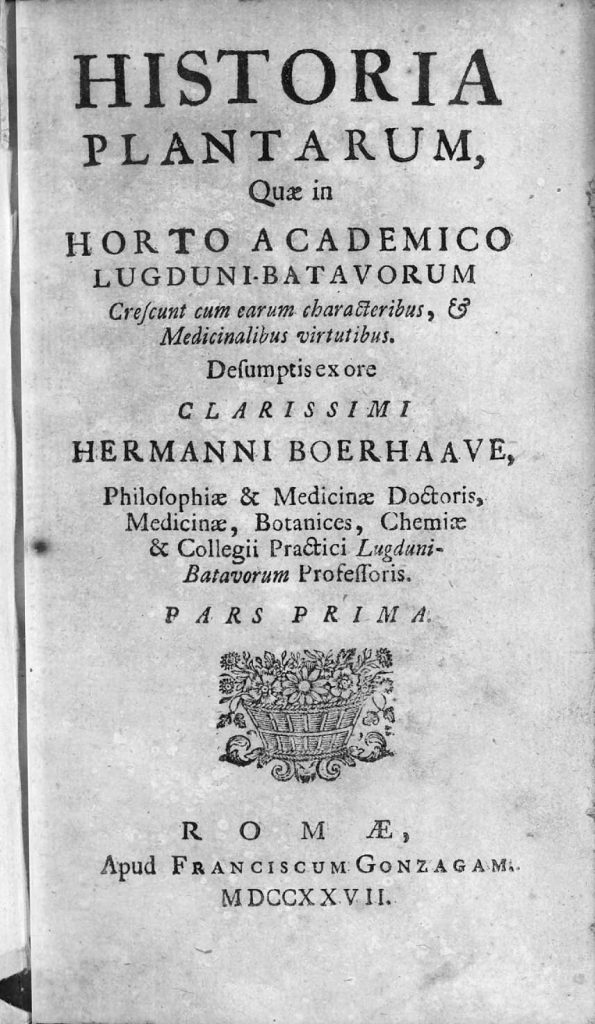

Historia plantarum quae in Horto Academico Lugduni-Batavorum crescunt, 1727

Medical contributions

Boerhaave devoted himself intensively to the study of the human body. He was strongly influenced by the mechanistic theories of René Descartes, and those of the 17th-century astronomer and mathematician Giovanni Borelli, who described animal movements in terms of mechanical motion. On such premises, Boerhaave proposed a hydraulic model of human physiology. His writings refer to simple machines such as levers and pulleys and similar mechanisms, and he saw the bodily organs and members as being assembled from pipe-like structures.[16] The physiology of veins, for example, he compared to the operation of pipes. He asserted the importance of a proper balance of fluid pressure, noting that fluids should be able to move around the body freely, without obstacles. For its well-being, the body needed to be self-regulating, so as to maintain a healthy state of equilibrium. Boerhaave’s concept of the body as apparatus centered his medical attention on material problems rather than ontological or esoteric explanations of illness.

Boerhaave’s teaching of his knowledge and philosophy drew many students to the University of Leiden. He emphasized the importance of anatomical research based on practical observation and scientific experiments. His concept of the bodily system took hold throughout Europe and helped to transform medical education in European schools. His insights aroused great interest among other critical medical thinkers, not least Friedrich Hoffmann, who strongly advocated the importance of physicomechanical principles for the preservation or indeed the restoration of health. As a professor at Leiden, Boerhaave influenced many students. Some in their experiments upheld and furthered his philosophy, while others rejected it and proposed alternative theories of human physiology. He produced a great many textbooks and writings through which the digested brilliance of his lectures at Leiden was circulated widely in Europe. In 1708, his publication of the Institutiones Medicare was issued in over five languages and went into approximately ten editions.

His Elementa Chemia, a world-renowned chemistry textbook, was published in 1732.

The mechanistic concept of the human body departed from the age-old precepts laid down by Galen and Aristotle. In place of a servile dependence upon teachings handed down from antiquity, Boerhaave understood the importance of establishing definitive findings through his own investigation, and by the direct application of his own methods of testing. This new reasoning expanded the field of Renaissance anatomy: it opened the way to reforms of medical practice and understanding in the field of iatrochemistry.

Boerhaave was closely befriended by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek who was also an inventor and skillful scientist and they collaborated closely at times.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (* 24. Oktober 1632 in Delft, Republic of the Seven Provinces – † 26. August 1723) was a Dutch researcher and inventor of (among many other things) the microscope.

He discovered microorganisms, including bacteria and protozoa, and is therefore called the “father of protozoology and bacteriology.“ He described the discovery of spermatozoa and studied them in numerous animal species. His observations made him opposed to spontaneous generation. In parallel with other researchers of his time, he discovered red blood cells and the capillaries as a connection between arteries and veins in the bloodstream. His research areas covered a wide range from medicine to botany.

He had no scientific or technical training and taught himself how to make and use microscopes. He shared the observations he made with his microscopes in over 300 letters to the Royal Society in London and to numerous other European personalities. Van Leeuwenhoek was the most important microscopist oft he 17th century

Rediscovered single-lens microscope built by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek; material silver and lens with a rated magnification of 248. Boerhaave also used these microscopes.

In 1676, the world saw a major shift in the way things were observed by human beings. A great discovery was made that was different from what the world had experienced before. It was comparable to the discovery of the Americas, only on the other side of the spectrum. While Columbus made a macro-level discovery, this discovery was on the micro-level, targeting the tiniest things on earth. It was the first time that human beings were able to see a world that had been unknown to them in tiny particles.

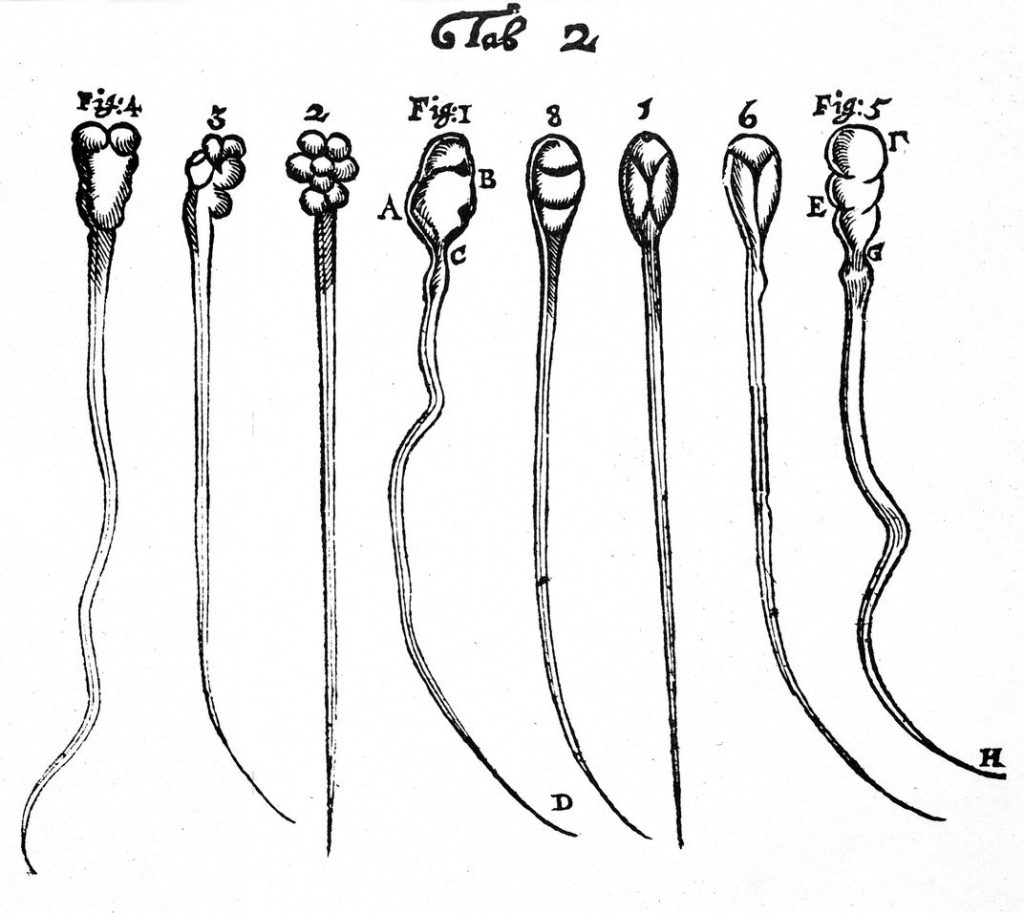

Here is a very good example of how not our sense organs mislead our perception but our expectations and interpretations (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe versus Emanuel Kant). Several times, when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek examined sperm and draw pictures of what he saw, he expected to find mini babies and the tail was the umbilical cord-to-be (fig: 3 and 4).

This might come as a disappointment to the courageous Dutch biologists (like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and Harm Boerhaave) who first looked upon sperm cells in their full glory in the 17th and early 18th centuries, using the then-revolutionary microscope. These early sperm scientists found themselves tasked with answering the most basic of questions, for instance: Are spermatozoa living animals? Are they parasites? And, does each sperm contain a tiny pre-formed adult human curled up inside?

In the 17th century, many researchers believed each spermatozoon contained a tiny, completely pre-formed human within it, as illustrated in this 1695 sketch by Nicolaas Hartsoeker. (Wikimedia Commons)

Leeuwenhoek’s early microscopic observations of human sperm, rabbit sperm, and dog sperm. (Wikimedia Commons)

Works by Boerhaave

Aphorismi de cognoscendis et curandis morbis, 1728

Oratio academica qua probatur, bene intellectam a Cicerone et confutatam esse sententiam Epicuri de summo bono (Leiden, 1688)

Het Nut der Mechanistische Methode in de Geneeskunde (Leiden, 1703)

Institutiones medicae (Leiden, 1708)

Aphorisms de cognoscenti’s et curanderas morbis (Leiden, 1709), on which his pupil and assistant, Gerard van Swieten (1700–1772) published a commentary in 5 vols.

Aphorismi de cognoscendis et curandis morbis (in Latin). Parisiis. apud Guillelmum Cavelier, via Jacobea, sub signo Lilii aurei. 1728.

Index plantarum quae in Horto academico Lugduno Batavo reperiuntur (in Latin). Leiden: Cornelis Boutesteyn. 1710.

Index alter plantarum quae in horto academico Lugduno-Batavo aluntur (in Latin). Vol. 1. Leiden: Pieter van der Aa (1.). 1720.

Index alter plantarum quae in horto academico Lugduno-Batavo aluntur (in Latin). Vol. 2. Leiden: Pieter van der Aa (1.). 1720.

Institutiones et Experimenta chemise (Paris, 1724) (unauthorized). (Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf)

Historia plantarum quae in Horto Academico Lugduni-Batavorum crescunt (in Latin). Roma: Francesco Gonzaga. 1727.

Elementa chemiae (in Latin). Vol. 1. Leiden: Severinus, Isaak. 1732.

Elementa chemiae (in Latin). Vol. 2. Leiden: Severinus, Isaak. 1732.

Historia plantarum quae in Horto Academico Lugduni-Batavorum crescunt (in Latin). Vol. 1. Amsterdam. 1738.

Historia plantarum quae in Horto Academico Lugduni-Batavorum crescunt (in Latin). Vol. 2. Amsterdam. 1738.

Historia plantarum quae in Horto Academico Lugduni-Batavorum crescunt, 1727

Elementa Chemiae, 1732

The standard author abbreviation Both. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[18]

References

Gerrit Arie Lindeboom (ed.), Boerhaave and His Time, Brill, 1970, p. 7.

Underwood, E. Ashworth. “Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years.” The British Medical Journal 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20395297.

Robert Siegfried (2002). From Elements to Atoms: A History of Chemical Composition, Volume 92, Issues 4–6. American Philosophical Society. p. 128

Mendelsohn, p. 287

Herman Boerhaave (1690). “De distinctione mentis a corpore” (PDF).

Gunn, Mary (1981). Botanical exploration of southern Africa: an illustrated history of early botanical literature on the Cape flora: biographical accounts of the leading plant collectors and their activities in southern Africa from the days of the East India Company until modern times. L. E. W. Codd. Cape Town: Published for the Botanical Research Institute by A.A. Balkema. p. 40. ISBN 0-86961-129-1. OCLC 8591273.

“Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2006.

Underwood, E. Ashworth (1 January 1968). “Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years”. The British Medical Journal. 4 (5634): 820–25. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5634.820. JSTOR 20395297. PMC 1912963. PMID 4883155.

Clow, Archibald & Nan L. Clow The Chemical Revolution, Batchworth Press, London, 1952.

Boerhaave, H., Atrocis, NEC description Prius, morbid historia: Secundum medical artis leges conscripta (Leiden, the Netherlands: Lugduni Batavorum Boutesteniana, 1724).

Boerhaave, Herman (1983). edited by Elze Kegel-Brinkgreve & Antonie Maria Luyendijk-Elshout. Boerhaaveìs Orations. Volume 4 of Publications of the Sir Thomas Browne Institute Leiden. Brill Archive. ISBN 9004070435, 978-9004070431

Principe, Lawrence (2007). New Narratives in Eighteenth-Century Chemistry: Contributions from the First Francis Bacon Workshop, 21–23 April 2005, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California. Springer, pp. 66–67

- Biglow, Orville Luther Holley (1817). The American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review, Volume 1. H. Biglow, p. 192

Hosack, David (1824). Essays on various subjects of medical science. New York Seymour. p. 113

Cook, Harold (2007). Matters of Exchange. New Haven: Commerce, Medicine, and Science in the Dutch Golden Age. p. 393.

Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe (second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–05. ISBN 978-0521425926.

Broman, Thomas (2003). The Medical Sciences. Cambridge: The Cambridge History of Sciences. p. 469.

IPNI. Both.

Guggenheim, K. Y. “Herman Boerhaave on nutrition.” The Journal of Nutrition 118, no. 2 (1988): 141-143. doi:10.1093/jn/118.2.141

Mendelsohn, Everett (2003). Transformation and Tradition in the Sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521524858

Rina Knoeff (2002), “Herman Boerhaave (1668–1783): Calvinist Chemist and physician.” History of Science and Scholarship in the Netherlands, Volume 3. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Underwood, E. Ashworth. “Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years.” The British Medical Journal 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. JSTOR 20395297

Further reading

Powers, John C. (2012). Inventing Chemistry: Herman Boerhaave and the Reform of the Chemical Arts. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-67760-6.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Herman Boerhaave.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Herman Boerhaave

“Boerhaave, Hermann”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911.

Samuel Johnson’s 1739 biography of him online: Life of Herman Boerhaave

Museum Boerhaave in Leiden, National Museum of the History of Science and Medicine

A recent discussion of Boerhaave’s Syndrome in the New England Journal of Medicine (subscription required)

Works by Herman Boerhaave at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Herman Boerhaave at Internet Archive

Works at Open Library

Herman Boerhaave at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

“Aphorisms de Cognoscendis et Curandis Morbis” (1709; “Aphorisms on the Recognition and Treatment of Diseases”)

“Elementa Chemiae” (1733) (Elements of Chemistry)

“A New Method of Chemistry” (1741 & 1753) (English Translation of “Elementa Chemiae” by Peter Shaw)

Javed Chaudhry’s Article about Herman Boerhaave