Alien-looking viruses discovered in Massachusetts forest:

microbes come in a variety of shapes, hinting at undiscovered ecological diversity

by

Prof. Dr. Robert Gorter

(with thanks to Science)

25th of July, 2023

Researchers have unearthed a trove of wonders in the soil of a Massachusetts forest: an assortment of giant viruses, unlike anything scientists had ever seen. The find suggests this group of relatively massive parasites has an even greater ecological diversity and evolutionary importance than researchers knew.

Giant viruses can exceed 2 micrometers in diameter, on par with some bacteria. They can also harbor immense genomes, which reach 2.5 mega-bases—larger than the genomes of far more complex organisms. Between the discovery of these impressively sized viruses in algae and the culturing of amoeba-infecting Mimi viruses, most of the research on the group has focused on viruses that inhabit freshwater environments. But DNA sequencing has long indicated that giant viruses are diverse and abundant elsewhere, too—especially in sediments and soils, which are estimated to host some 97% of all the viral particles on Earth. Indeed, genomic sequencing of the soils of Harvard Forest—a roughly 16-square-kilometer area west of Boston—indicated the presence of numerous, novel giant viruses.

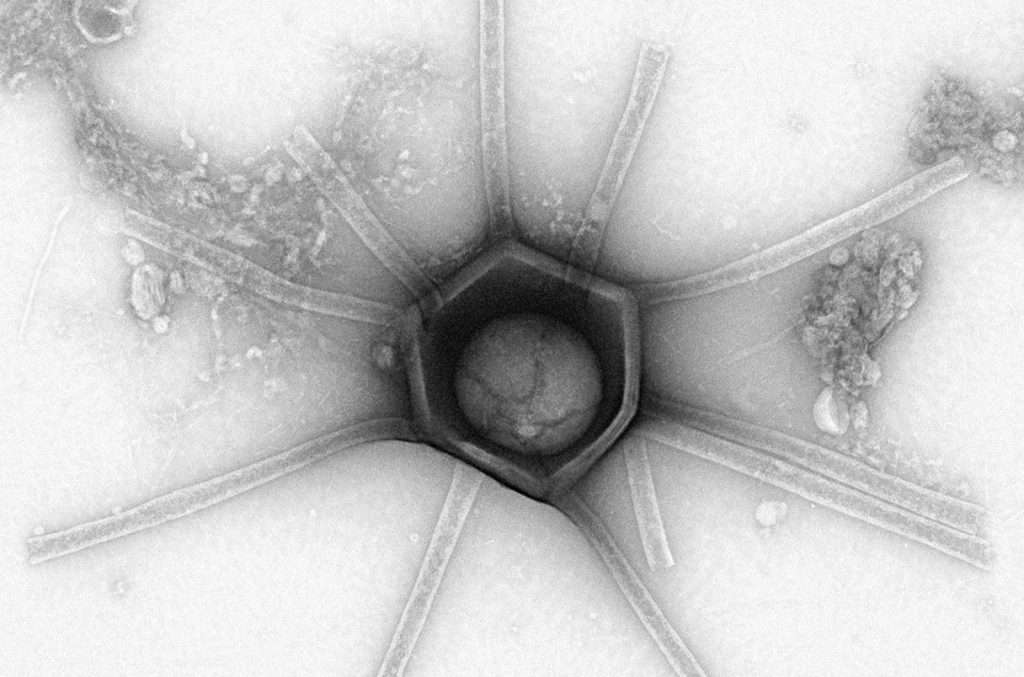

Now, electron microscopy has allowed scientists to see what others had only sequenced. The diversity of forms was astounding, they report in a bioRxiv preprint. Not only did the researchers see the 20-sided icosahedral shapes they expected, but they also spotted ones with myriad modifications—tails, altered points, and multilayered or channeled structures abounded. There were even viruses with long tubular appendages, which the team dubbed “Gorgon” morphology (above). Furthermore, many of these putative viral particles were coated with almost hair-like projections, which varied in length, thickness, density, and shape.

Formularbeginn

Formularende

The findings suggest virologists have much to discover about how giant viruses interact with their host cells. That likely means the ecological roles these viruses play in soils—and elsewhere they’re found—are woefully underappreciated.

Prof. Gorter: what is often underappreciated is the fact that viruses played a major role in developing higher animals and humans; and complex organelles.

Giant virus genomes discovered lurking in DNA of common algae: viral stowaways could be enhancing the survival of algae, and even their evolution

Green algae (pictured) can sometimes host the DNA of entire giant viruses in their genomes. AMI IMAGES/SCIENCE SOURCE

In 2003, scientists discovered something huge, literally, in the virus world: viruses so big they could be seen with a standard microscope. These massive parasites were considered rare at the time, but they’ve since proved more common than anyone expected. Now, researchers have found entire giant virus genomes embedded in the genomes of several common algae. The find suggests this strange viral group is even more prolific—and potentially influential—than scientists thought.

“The sheer amount of DNA and the diversity of genes contributed by these viruses to their hosts is staggering,” says Cedric Feschotte, a genome biologist at Cornell University who was not involved with the work. This “big injection of genetic material” could influence everything from the host’s metabolism to its very survival.

Typical viruses don’t have enough genes to live on their own. Instead, they must rely on the machinery of their hosts, whether those be bacteria, human cells, or other organisms. Viruses reproduce by having the host replicate their genetic material and make proteins needed for copies of themselves. So it was surprising earlier this year when researchers discovered that giant viruses contain genes they don’t seem to need—namely, stretches of DNA important for cell, but not viral, metabolism.

Formularbeginn

Formularende

At Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, microbiologist Frank Aylward and his postdoc Mohammad Moniruzzaman followed up on this mystery by matching genes found in giant virus DNA to those previously documented in other genomes. Viral matches “kept popping up in algal genomes,” Aylward recalls. So the duo and their colleagues systematically looked through genomes representing all of the sequenced DNA from the group of algae called Chlorophytes. An entire giant virus was genetically present in the DNA of a dozen of these species, the team reports today in Nature.

In all, the viruses added between 78 and 1782 genes to the algae. Two algae even had the whole genomes of two giant viruses in their DNA, in one case making up 10% of the algae’s total gene count.

It’s not clear why these viruses sneak their DNA into their host’s genome, instead of just replicating inside the cell. It may be a way for the virus to ensure that its genetic material will be passed down from generation to generation. HIV and other viruses also integrate their genes into human DNA—one reason they are difficult to eliminate by the immune system or drugs.

Some of these giant viruses have likely been part of the algae for a long time, the researchers found, perhaps millions of years. Indeed, some viral DNA has acquired noncoding DNA called introns within their genes. And some of their genes are now duplicated or missing, changes that are unlikely to occur in viruses simply floating around inside algal cells.

“They make a solid case that the viral sequences they identified are, in all likelihood, part of their host genomes,” says Matthias Fischer, an environmental virologist at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research.

“I’m surprised that such giant virus [incorporation] can occur and is widespread,” adds Chuan Ku, a microbiologist at the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology. Ku, who has unraveled the life cycle of a giant virus that infects tiny alga called Emiliania huxleyi, says, “It would be interesting to investigate if such [incorporation] has long-lasting effects on [host] genome evolution.”

The viral DNA present in algae can even include genes hijacked from other algae. The giant viruses may therefore be a way to transfer genes among species, says Andrew Roger, an evolutionary biologist at Dalhousie University. All of this new DNA can enable the host genome to take on new functions that improve the alga’s ability to survive and may have shaped the group’s diversity and distribution, he says.

“These interactions have been going on since the origins of life,” Fischer adds. “And they continue to play a big role in cellular evolution.”