A horse suffering from neurological symptoms caused by EHV-1 is treated in Valencia, Spain.

Deadly viral outbreak ravages European horses

by

Christa Lesté-Lasserre

Commentary by Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.

March 24th, 2021

Late last month, an international horse jumping competition in Spain that usually offers a sunny getaway for elite riders took a grim turn. A disease outbreak sickened scores of horses, leaving many so weak they couldn’t stand and others exhibiting unusually aggressive behavior. At least 17 animals have since died; others have had abortions or needed surgery to repair organ damage.

The equestrian world is bracing for worse to come. Before researchers were able to identify the outbreak’s cause—a known pathogen named equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1)—some 600 of the 750 horses participating in the event were already heading home, threatening to spread what officials already call the most serious EHV-1 outbreak in Europe in decades. In a bid to contain the damage, the International Federation for Equestrian Sports (FEI), which oversees international equestrian competitions, has canceled all European events—including its World Cup—through at least mid-April. Horse owners, meanwhile, are frantically trying to vaccinate and isolate their horses.

For scientists, the outbreak has raised a host of questions. They are examining why EHV-1, a familiar virus that typically produces milder symptoms, appears to have hit these animals, particularly mares, unusually hard. Some are wondering whether drugs or the vaccine against EHV-1 itself may have played a role. “Our top priority must be to deal with the immediate impact of this terrible virus,” says Göran Åkerström, veterinary director of FEI. But, “It is also crucial that we … expand our epidemiological data.” A special FEI working group to study the outbreak had its first meeting on the 18th of March, 2021.

Researchers say conditions at the month-long competition, held in Valencia, Spain, were ripe for an outbreak of EHV-1, which is primarily spread by exhaled droplets. The horses were housed in tightly packed stalls, and “All it takes is for one horse carrying a latent virus to have some sort of stress, and his virus gets activated and starts shedding,” says equine disease specialist Lutz Goehring of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Sick animals soon overwhelmed an equine hospital at the nearby CEU Cardenal Herrera University, says Ana Velloso Álvarez, a veterinarian there. Exhausted medics were treating up to 20 animals simultaneously, with many horses hoisted in slings, literally hanging between life and death.

Studies have found that nearly all horses have been exposed to at least one of EHV-1’s five major strains, and animals can carry the inactive viruses for years. Active infections usually cause fever and mild respiratory disease, sometimes abortion. One especially worrying variant, known as type 1, can cause serious neurological damage, rendering horses wobbly or unable to stand. Occasionally, it kills them.

Most outbreaks affect just a handful of horses before a farm is quarantined and disinfected. And less than 15% of infected animals typically exhibit neurological symptoms. But in Valencia up to 40% of sick horses have shown signs of neurological damage, Álvarez says. And, in an unusual twist for EHV-1, each horse had its own cocktail of problems. Some had intestinal blood clots and needed surgery. Others had swollen legs, walked like they were drunk, or exhibited unusual behavior. “This is completely different from what we’re used to [with EHV-1],” Álvarez says.

Genetic sequencing suggests the outbreak wasn’t caused by a new strain of EHV-1. That has researchers looking at other factors that might have worsened outcomes. One is travel. Some horses spent up to 3 days journey to the event, and such long trips can be “a huge stressor,” says Barbara Padalino, an equine scientist at the University of Bologna. Recent studies by her team have shown that after just a 12-hour trip, a horse’s immune defenses against EHV-1 drop, increasing the chance of infection.

Other scientists are examining the role of sex. About 80% of the most severe Valencia cases involved mares, Álvarez says. Some researchers wonder whether medications used to stop the mares’ reproductive cycles—a treatment some riders think makes a horse easier to handle—might have contributed to illness. One popular drug, Altrenogest, is based on progesterone, which has been shown to weaken immune function, notes Christine Aurich, an equine gynecologist at the Graf Lehndorff Institute in Germany.

Researchers are also scrutinizing the EHV-1 vaccine, which has a spotty record of preventing disease and requires booster shots every 6 months. Many of the sick horses had been vaccinated, Åkerström says—but past studies have hinted that horses may be at higher risk of neurological symptoms in the weeks after vaccination. FEI’s working group is gathering vaccination records, as well as infection and symptom data, in hopes of clarifying such issues—and developing better ways to treat and prevent future outbreaks.

Robert Gorter: Horses like these are trained and pushed for extreme activities like running faster and jumping higher. To increase muscle strength and endurance, horses are fed high protein food. To reach a high level of proteins, horses are fed with high protein-containing feed; from plant and from animal sources.

How much protein does a horse need?

A horse’s requirement for protein is determined by the animal’s stage of development and workload.

Some general recommendations are listed below (please note, intakes mentioned are merely for the purposes of illustrating what is needed to meet protein requirements alone, but will likely not meet requirements for other nutrients).

A mature horse (average weight of 1100 pounds) needs about 1.4 pounds of protein a day for maintenance, early pregnancy, or light work. The horse usually ingests at least this much protein by grazing or eating grass hay (dry matter intake of about 22 pounds).

A mature horse doing moderate to heavy work needs about 2 to 2.15 pounds of protein a day. An owner could feed 22 pounds of grass or hay and add 2 to 4 pounds of fortified feed to meet the protein requirement.

A broodmare in late pregnancy needs high-quality protein to build placental and fetal tissue. Forage with a moderate percentage of alfalfa may provide this protein, but mares on marginal grazing benefit from the addition of 2 to 4 pounds of concentrate containing 13 to 16 percent protein.

A broodmare in the first three months of lactation requires about 2.75 pounds of protein each day. Besides grass or hay, she might need up to 7 pounds of fortified feed to ensure this much protein in her diet.

Protein needs are lower for broodmares in late lactation (after three months). Grass or hay and 2.5 pounds of fortified feed would supply a requirement of about 2 pounds of protein.

Weanlings weighing 550 pounds need about 1.6 pounds of protein. Because these younger horses eat less grass or hay, grain can be increased to 7 pounds a day.

Yearlings weighing 850 pounds eat more grass or hay and require about 4.5 pounds of concentrate to bring protein intake to 1.75 pounds a day.

To meet the protein demands of young horses in training, owners may need to feed as much as 7 pounds of concentrate along with 14 pounds of hay to provide the 2 pounds of protein that are required.

What is meant by high-quality or low-quality protein?

All horses need protein, but not all protein is the same. Protein is made up of different amino acids, some of which can be synthesized within the horse’s body. Amino acids that cannot be synthesized are called essential amino acids and must be supplied in the feed. High-quality protein is that which supplies the essential amino acids in the proper ratios. It is possible for a horse to eat enough low-quality forage to meet its crude protein requirement and still not be properly nourished.

Why is protein so important for young horses?

Lysine, methionine, and threonine are the most important amino acids which must be provided in equine rations. Diets for young horses need to include sufficient lysine to support growth and development.

The protein in mare’s milk is a rich source of lysine, as is the soybean meal included in some concentrates. Legumes such as alfalfa also provide significant amounts of lysine, while grasses and most cereal grains contain lower percentages of this important nutrient.

Do older horses need protein?

Adult horses need protein only for the repair and maintenance of body tissues, so their total requirement is fairly low. Many mature horses get all the protein they need (about 10% of the diet, on average) from grass or hay. Owners can confirm that this need is met by having pastures and hay analyzed.

If the analysis shows that the protein level is below 10%, an easy way to boost protein consumption is to offer some alfalfa hay along with, or instead of, the low-quality forage that has been provided.

Heavily exercising horses have a higher need for protein than maintenance horses, and the protein requirement is highest for late-pregnant broodmares and those in the first three months of lactation.

If these horses also require extra energy, the addition of concentrated feed to the diet can increase the intake of both energy and protein.

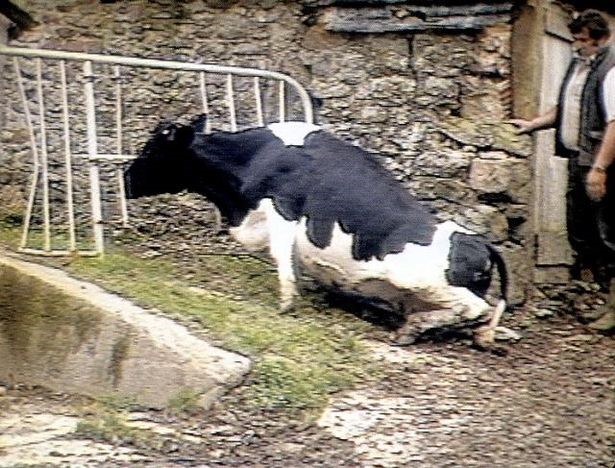

A Mad Cow (BSE)

Now, here is the catch: feed is fortified with animal proteins, like fishmeal. Cows and horses are typical vegetarians and if they are forced to eat fishmeal this will lead to immunodepression and an increase of (viral) infections.

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease, is a neurodegenerative disease of cattle. Symptoms include abnormal behavior (aggressive), trouble walking, and weight loss. Later in the course of the disease, the cow becomes unable to function normally. The time between infection and onset of symptoms is generally four to five years. Time from onset of symptoms to death is generally weeks to months. Spread to humans is believed to result in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (vCJD). As of 2018, a total of 2310 cases of vCJD in humans had been reported globally.

Rudolf Steiner ca. 1905

Rudolf Steiner, PhD (1861-1925) warned multiple times for this in his lectures on organic and bio-dynamic agriculture courses during the second decennium of the 20th century. He literally states, that when one forces cows, horses, and other cattle with animal products, they will turn mad (German: “irrsinnig”): he literally says that cows will urn mad (“Mad Cow Disease”). All vegetarian animals (cattle and horses) will become immunosuppressed by long-term exposure to feed-containing animal proteins. New kinds of diseases would appear among these animals.

A cow with BSE